|

On October 4, two prominent architectural photographers visited the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as part of a month-long tour of vacant American theaters. Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre, both from Paris, spent several hours photographing the auditorium, Shrine of the Immortal, and backstage area in order to raise awareness of the building's condition and potential. This week they shared the images with us and generously gave us permission to use them on our websites.

Marchand and Meffre's work has previously been exhibited in France, the UK, the Netherlands, Monaco, Australia, and the US. They have been featured in the New York Times, TIME, and Le Monde. To view their photographs, visit www.marchandmeffre.com/theaters. On Tuesday, Worcester's City Council voted unanimously to establish the Downtown Worcester Business Improvement District, the first in the city. Business and property owners within the district will contribute to a fund for projects such as snow and litter removal, marketing, and beautification efforts. The BID has been authorized for five years and may be renewed afterwards. According to Hanover Theater president and CEO Troy Siebels, it is "an important tool for having a vibrant downtown...You will see and feel the difference."

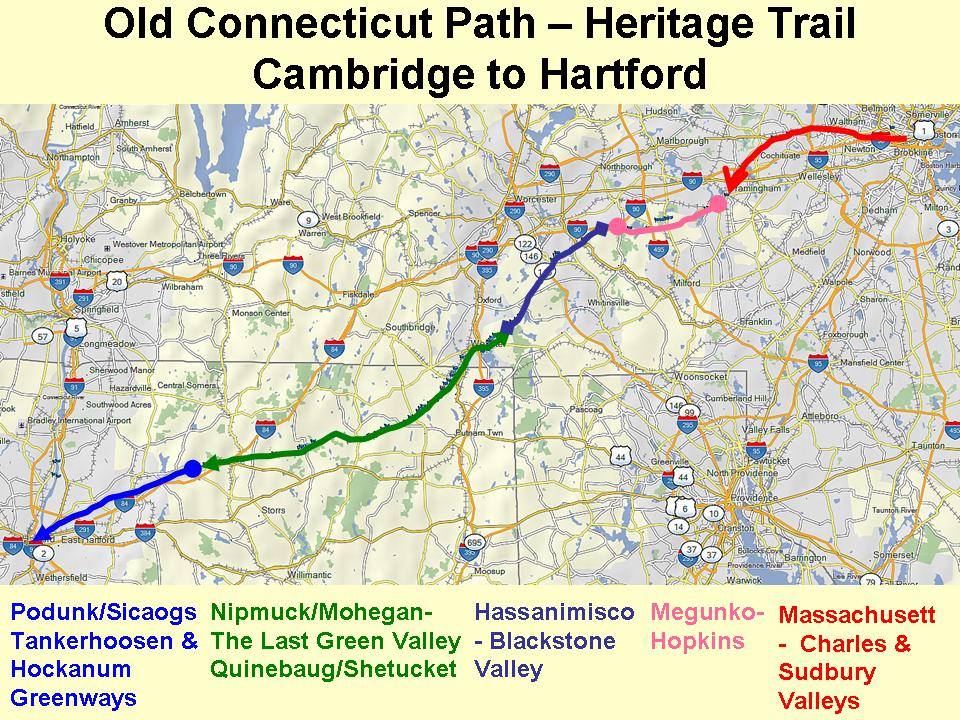

Read the full story here: https://www.telegram.com/news/20181120/worcester-city-council-approves-downtown-business-improvement-district When English colonists arrived on the shores of Massachusetts four hundred years ago, they beheld an unfamiliar territory almost devoid of features that might have reminded them of home. There were no carriage paths or cattle pastures, no rooting hogs or crowing roosters, no church steeples or tolling bells. Steep drumlins loomed above the coast, beyond which forests and marshland stretched westward. Mountain lions skulked behind boulders. Wolves howled at night. To settlers accustomed to a treeless countryside subdued beneath the plow, New England was a “vacant wilderness…a place not inhabited but by the barbarous nations.” Little did they understand the way of life that those nations had created over the past three thousand years. Massachusetts during the Woodland Period (3,000-400 BP) was not a pristine wilderness, but an increasingly manipulated landscape home to tens of thousands of Native Americans. As post-glacial sea levels stabilized, Woodland peoples adopted new patterns of habitation and movement that spurred agricultural, technological, and cultural development. Many gravitated toward coastal areas and established long-term seasonal settlements, where they began to plant crops. Initially, they selectively bred weedy vegetation including sunflower, goosefoot, and sumpweed, and boiled the seeds in porridges. By 1000 CE, Central American cultivars – maize, squash, and beans – had arrived in New England and were becoming increasingly important in local diets. Woodland peoples’ migratory lifestyles enabled them to diversify their food sources. Archeological evidence, such as shell middens (ancient trash heaps) on Spectacle Island, suggests that Native Americans settled in large villages during the spring and fall, where they planted and harvested crops, fished, clammed, and hunted, and held political meetings (indeed, in 1614, explorer and colonist John Smith recorded that Native peoples grew maize on the Harbor Islands). During the summer and winter, many villages disbanded. Residents moved to smaller settlements in the region to better exploit food sources while crops ripened or the ground lay frozen. Agriculture transformed the Massachusetts landscape. Though the area remained heavily forested at the time of European contact, patches of cleared ground reflected repeated seasonal use. Native Americans believed that they owned the use of land, rather than the land itself; instead of adopting permanent farming sites, they tilled soil until it was no longer fertile (about eight to ten years) and then relocated. Women cleared new land by setting fires at the base of trees to kill them, and, once the dead wood fell, by burning it away. This method, along with the practice of burning fires all night during both the winter and summer, meant that localized deforestation was common. Thousands of acres near Boston were treeless by 1630; elsewhere, the whitened trunks of girdled trees surveyed cornstalks intertwined with bean and squash vines. Far from a “vacant wilderness,” Massachusetts was an intensively used homeland. Fire enabled local tribes not only to grow crops and stay warm, but also to hunt, gather, and travel. English colonists were astounded that Woodland peoples set large ground fires in the forests during the spring and fall, and were equally impressed with the effects. The woods near Native villages tended to be clear of tangled undergrowth. The widely spaced trees, grass, and pioneering berry bushes created a park-like setting that attracted game, facilitated hunting, and limited the risk of future fires burning out of control. The relative openness of Woodland Period forests also eased long-distance travel. Overland routes developed over thousands of years, crisscrossing tribal territories. Among the most famous was the Old Connecticut Path: it began near present-day Cambridge, following the Quinobequin ("meandering," later Charles) River through Massachusett territory before curving southwest into Nipmuck land. From there, it passed south of present-day Worcester and continued on to the area along the Connecticut River that would eventually become Hartford. (Parts of the route remain heavily traveled today – the Old Connecticut Path is now known as MA Route 9 and MA Route 126.) Europeans arriving in New England did not have to build everything from scratch. They entered a region that already had the equivalent of an international highway system, which they used to expand their settlements. At the dawn of the seventeenth century, modern Native tribes were well-established in Massachusetts. They occupied defined homelands and engineered the environment to facilitate a migratory lifestyle that maximized the yield of local resources. They were also increasingly aware of the world beyond the Atlantic – a world that appeared on the horizon as billowing ship sails, dropped anchor and fishing lines in Massachusetts Bay, and, until 1620, never stayed for long.

E-sports is rapidly becoming a major athletic and economic player. Can the city of Worcester get in the game early with the Aud redevelopment project? “The games that are competitively viable in the collegiate sphere have real depth, have deep levels of strategy, and require strategic teamwork and require real mastery to be successful — and not just by yourself, within a team environment and through using tactics.” Read the full New York Times article here.

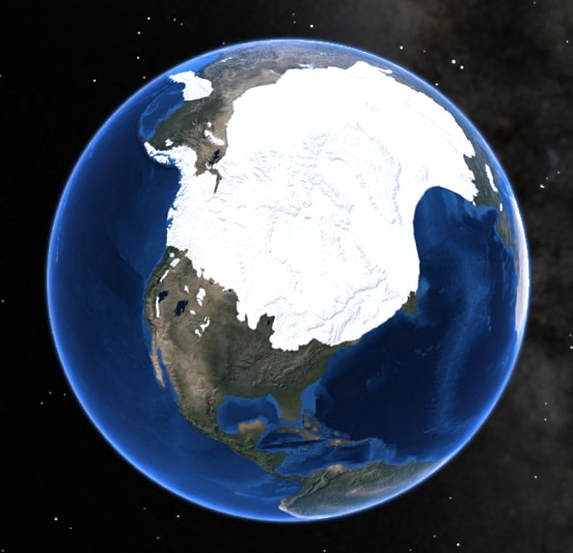

Eighteen thousand years ago, Worcester was smothered beneath 1,800 feet of ice. The blue-white wasteland extended in all directions, burying Mount Wachusett and slowly scouring away the soft sedimentary rock of more recent eons from ancient, underlying schists. Locked in an ice sheet that stretched from the Arctic to present-day New Jersey, Worcester County was unrecognizable: a crevassed expanse of silence reaching toward the rising sun and tumbling into Atlantic waters that were hundreds of feet lower than they are today. The Laurentide ice age was the culmination of one million years of glaciations that dramatically altered the New England landscape. Fluctuating temperatures during the Pleistocene resulted in glaciers repeatedly advancing and retreating across the region. The most recent major ice age – which, according to geologists, is still occurring – began 25,000 years Before Present (BP). Long winters and cool summers caused more snow to fall than melt. The snow eventually compacted under its own weight into an ice sheet that left a rugged legacy in Massachusetts. As the glaciers moved, they accumulated silt, gravel, and even boulders; water seeped into cracks in the bedrock, froze, and expanded, breaking off large chunks of stone that were carried away by the ice. When the ice began to melt around 17,500 BP, it deposited these sediments unevenly throughout the landscape. Leisurely hikes in Worcester County often reveal glacial features: Dexter Drumlin, Purgatory Chasm, eskers in Worcester’s Hadwen Park, erratics in Holbrook Forest, and innumerable wetlands, often the result of poor drainage in areas of tightly packed glacial till. Gradually the ice sheet receded from the region. By 14,000 BP, the barren earth was once again exposed to the sky. Another thousand years would pass before humans braved the tundra of Massachusetts. Archaeological evidence suggests that Paleo-Indians initially settled near major rivers and bodies of water. In 2015, an amateur archaeologist unearthed a small, triangular piece of flint in a Northampton potato field. He recognized it as a what it was right away – a Clovis point arrowhead. Researchers soon confirmed that the arrowhead was 12,800 years old, one of the oldest artifacts ever discovered in the state. Other archaeological sites in Western Massachusetts indicate that Paleo-Indians used the lush Connecticut River Valley as a seasonal hunting ground. Although similar prehistoric evidence is scarcer in Worcester County, fluted points have been found in the Chicopee and Blackstone River Drainages. Local Paleo-Indians likely lived in small, migratory bands, hunting mastodon as well as smaller game and fishing in the region’s many streams and ponds. They adapted to a warming climate that turned the tundra into a vast boreal forest, which, in turn, gave way to hardwoods. By 9,500 BP, ecological change and over-hunting had eradicated the megafauna and created a landscape that would shape humans’ lives for the next nine millennia. Worcester County became more densely populated during the Archaic Period (9,000-3,000 BP). Human settlement spread to present-day West Brookfield, Westborough, and other areas, where archaeologists have discovered projectile points, stone tools, and burial sites. Like their ancestors, Archaic peoples were predominantly hunter-gatherers. They travelled between seasonal hunting grounds in pursuit of game and were deeply familiar with the movements of birds and fish. They mined quartzite from local quarries to fashion weapons and tools, littering the ground with stone flakes that enable today’s archaeologists to identify sites of habitation (such as the Cracked Rock rockshelter in Millbury). Throughout this period, Archaic cultures evolved. The ancient residents of Worcester County adopted new styles of stone and bone craftsmanship as technology improved and fashions changed. They also came to depend more heavily on plant foods, giving rise to the development of local agriculture 3,000 years ago. This milestone was one of many that marked the transition from the Archaic era to the Woodland Period (3,000-450 BP). The millennia preceding European colonization would witness the genesis of contemporary Native American tribes and of the vibrant civilizations that greeted English settlers on the shores of the New World.

Adaptive reuse projects and restaurants are the top targets for retail investors today. By Kelsi Maree Borland | October 29, 2018 at 04:00 AM Heslin Holdings has announced plans to invest $75 million in equity into retail assets over the next 12 months. The firm says that there are still plenty of opportunities in the retail market, despite headlines, particularly in adaptive reuse projects, restaurants and daily needs categories. Heslin will focus these investment dollars on growth markets West of Texas.

“Retail is being gentrified. It might have one use and then the next day is reused through adaptive reuse,” Matthew Heslin, principal and CEO with Heslin Holdings. “For example, now you are seeing a need for more last-mile distribution, and people are taking older grocery stores and turning them into distribution hubs for localized distribution. We look at it from a multitude of different views. Adaptive reuse of repurposing retail is one big opportunity. Next, the quick service restaurants and fast food is not going away, and every day household needs, including the dollar stores and the discounters, are doing well. We are focused on using those as part of our retail expansion.” While the firm sees opportunities in retail, the need to place remaining capital was the impetus for the 12-month, $75 million allocation. “We have capital left in our pipeline that we need to execute on,” explains Heslin. “So, it was driven both by capital allocation and opportunistic deals that are in front of us right now.” Heslin is seeking retail opportunities in growth markets west of Texas, and is specifically looking to markets with population and GDP growth and strong employment. “From a macro perspective, we are looking for stable markets with GDP growth, and that has stable employment, diversified GDP and population growth,” says Heslin. “Denver is a good example of that. It is a market with 50,000 millennials moving in and more than 1 million millennials in the market. It has biotech, technology, finance industries. That is a market in particular that we like.” The $75 million is equity will be paired with debt on a case-by-case basis. Heslin has the ability to purchase assets in all cash as well. “We have different opportunities to finance our deals,” says Heslin. “We do all-cash deals, or we do lines of credit, bridge financing and permanent financing. It depends on the asset and on our investors’ appetite. We use different financing options for different opportunities and assets.” Overall, Heslin says the firm is cautiously optimistic on the retail investment market, even with rising interest rates and an extended cycle. “There are opportunities in every cycle,” he says. “We are returning to normalized interest rates and cap rates, which means they will be rising over the near and long term. A prudent investor is going to be planning for that and underwriting to those eventualities. It is important to underwrite flat rents with inflationary expense growth.” Source: https://www.globest.com/2018/10/29/where-retail-investors-are-spending-money/?slreturn=20180930104323 It's no secret to Worcester residents that their city is booming - and now the the truth is even more widely known, thanks to NPR:

https://www.npr.org/2018/10/23/658263218/forget-oakland-or-hoboken-worcester-mass-is-the-new-it-town?utm_source=facebook.com&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=npr&utm_term=nprnews&utm_content=2051 Worcester already has a lot to offer - culture, community, colleges, commerce - and it may soon have even more. The Telegram & Gazette reports on efforts to establish a Business Improvement District downtown: A group of downtown property owners is asking the City Council to allow the establishment of a Business Improvement District that would encompass roughly 78 acres downtown. Such a district, which is allowed under state law, would provide business and property owners with a legal mechanism for collecting and allocating self-imposed fees via an annual assessment. The money could be used to fund a variety of “public realm” improvements in the district, such as enhanced street sweeping, sidewalk power washing, sidewalk snow removal, landscaping, removing stickers and other paraphernalia from streetscape furniture, public safety enhancements, beautification projects and marketing. Read the full story here: https://www.telegram.com/news/20181015/bid-for-downtown-improvement-district-heads-to-worcester-council

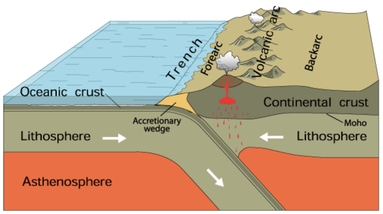

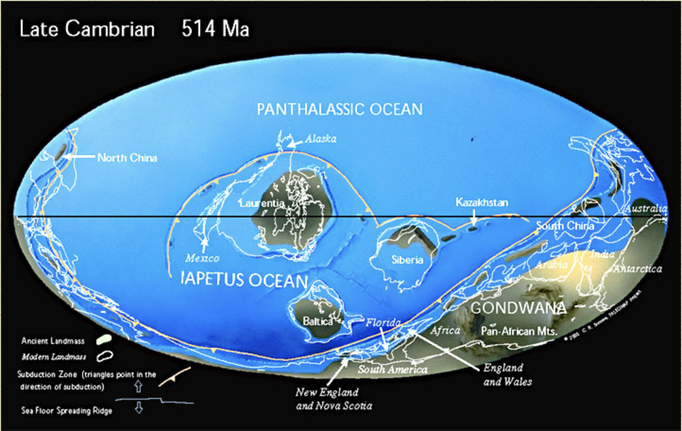

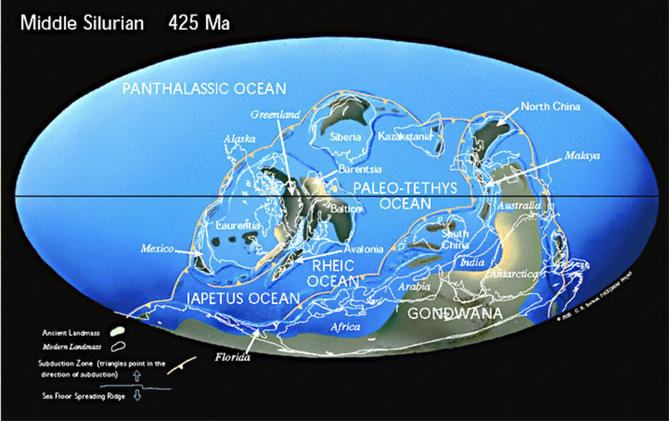

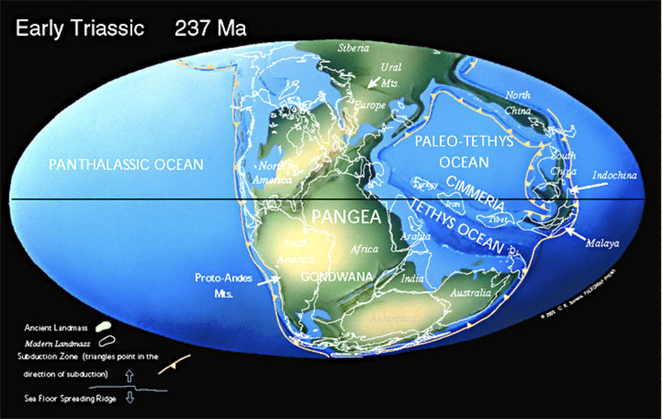

Subduction. Courtesy of USGS. Subduction. Courtesy of USGS. Imagine a world where South America is at the South Pole, Siberia, along the Tropic of Capricorn, and Greenland, at the Equator. In this world, Florida is a frigid strip of coast connecting South America and Africa. Canada bakes beneath a bright equatorial sun. The rest of North America is a scuba-diver's paradise – assuming scuba-divers numbered among the primitive, single-cell organisms that existed 550 million years ago. Welcome to the Late Precambrian, an era of dramatic geological change and the beginning of New England’s story. At this point, the earth was 3.5 billion years old. It had already experienced multiple episodes of continental drift, volcanism, and glaciation. The Grenville Mountain chain, formed during an earlier period of tectonic collision, had eroded. All that remained was a small layer of bedrock and a large amount of sediment that would eventually become western Massachusetts. Three major continents contained most of the planet’s land mass: Laurentia, Baltica, and the supercontinent Gondwana, whose coastline roiled with volcanic activity. The earthquakes and lava flows were symptoms of tectonic subduction (when one tectonic plate dives beneath another) and rifting (when two plates diverge). Over time, these subterranean stirrings formed the Avalon mountain range and Boston Rift Basin off the coast of present-day South America. We now call this region New England. As Earth entered the Cambrian Period, Avalon broke away from Gondwana. Sediments filled the rift basin and compressed into the Cambridge Argillite and Roxbury Conglomerate (puddingstone) rock formations underlying Greater Boston today. Between 430 and 390 million years ago, Avalon collided with Laurentia, forming the Northern Appalachians. This period of tectonic uplift coincided with rising oxygen levels and an explosion of multicellular life. Complex organisms spread across the globe as New England rose from the depths of the ocean. Over the succeeding eons, the planet’s crust continued to transform. The continents collided again 250 million years ago to form Pangaea, lifting the Appalachians to Himalayan heights, and then separated fifty million years later. This period of rifting created today’s continents and instigated more lava flows. We can still see evidence of this geological turbulence in the igneous and metamorphic rocks of Worcester County. Volcanic activity subsided as the continents drifted to their present locations. Massachusetts was thereafter shaped by deposition, weathering, and erosion. Temperatures rose, fell, and rose again, causing frequent glaciations that carved the Northeastern bedrock. Meanwhile, life evolved. The region was alternately submerged in shallow seas teeming with crustaceans and fish, and raised high and dry, a coastal forest where dinosaurs roamed. By the time Homo sapiens arrived in New England twelve thousand years ago, the region was a frozen tundra. The latest Ice Age scarred the landscape with eskers, dimpled it with kettle ponds, and pimpled it with erratics – a rugged topography that determined where humans settled, and upon which they would eventually unleash their transformative might.

The Architectural Heritage Foundation is thrilled to announce the launch of our Instagram and Twitter pages! Follow us:

Instagram: ahfboston Twitter: @AHFBoston |

AuthorArchitectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) is working to preserve and redevelop the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as a cutting-edge center for digital innovation. Archives

May 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed