|

A recent Wall Street Journal article highlighted Worcester's Becker College as a national leader in in the rapidly growing esports industry. Esports, which involves live and streamed multi-player video game competitions and is tied closely to game production, has achieved international popularity rivaling that of major league sports in the United States. The industry is projected to grow to $1.7 billion by 2021, and its viewership, to half a billion people. The Journal noted that Becker, already renowned for its program in video game design, is the first institution of higher education in the country to offer an Esports Management degree.

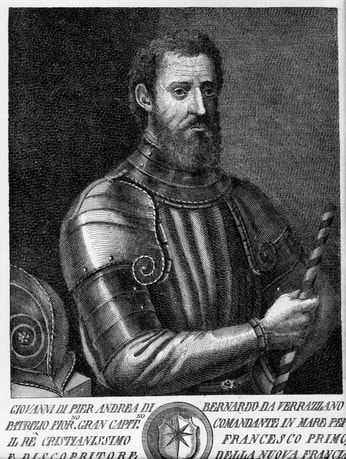

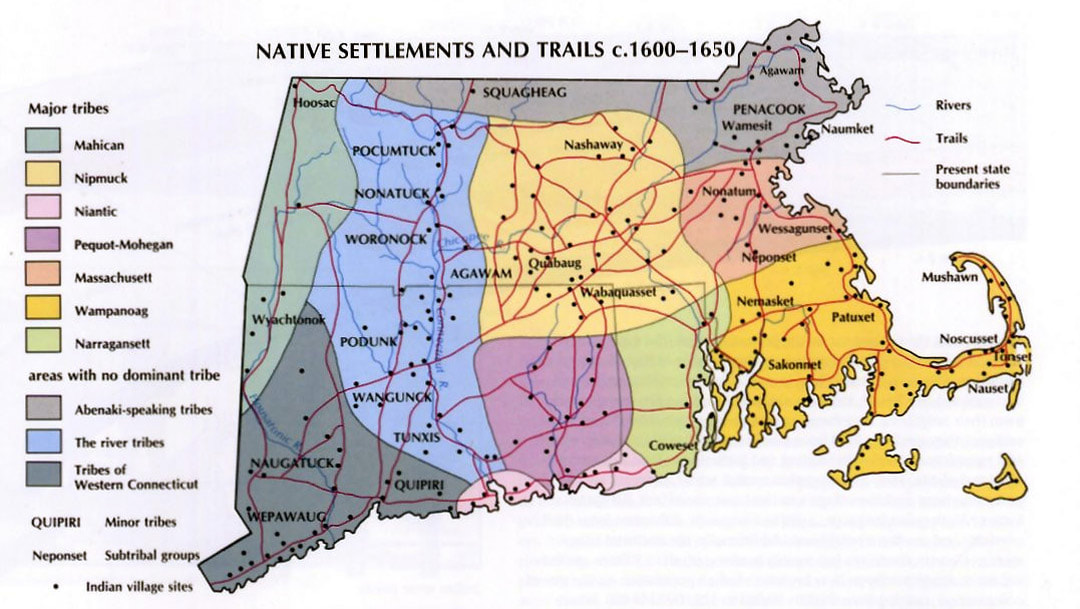

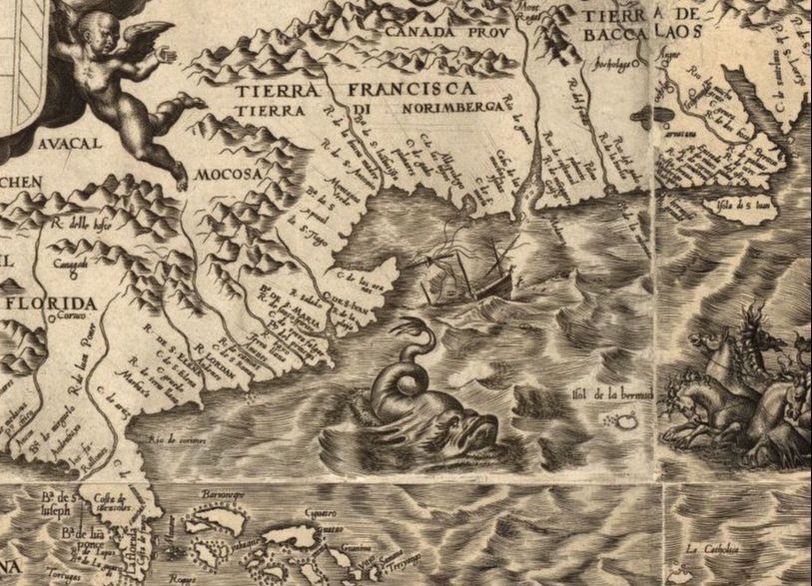

The Architectural Heritage Foundation is partnering with Becker College to study potential uses for the Aud. The school has contributed its expertise in interactive media to developing a vision of the Aud as a cultural and educational institution devoted to technological innovation. Read the Wall Street Journal article here: http://www.wbjournal.com/article/20181210/PRINTEDITION/312079995/1004?utm_source=enews&utm_medium=DailyReport&utm_campaign=Thursday In popular memory, the modern history of Massachusetts began in 1620 with a group of English religious zealots. These men, women, and children are said to have ventured into an unknown region of the New World, a wilderness home to Native Americans who previously had never seen a European face. Massachusetts Bay, the story goes, was discovered, explored, and exploited by English dissidents. But popular memory often plays tricks. The Pilgrims encountered a region that was neither unmapped nor unaware of the wider world. Rather, it had played a role in the imperial Atlantic power struggle for decades. The coastal plains and rolling hills that would become so important in United States history were and remain home to many Algonquian-speaking tribes. Massachuseuck territory, named for the sacred Great Blue Hill (Massachusett, “Big Hill Place”), stretched across present-day Greater Boston. To the west lay Nippenet (“Freshwater Pond Place”), land of the Nipmuck. Their neighbors included the Wampanoag along the Cape; the Pocumtuck, Nonatuck, Woronock, and Agawam along the Connecticut River; the Muheconeok in the Berkshires; and the Penacook and Squagheag to the north. Dozens of long-distance trails connected villages throughout New England, facilitating trade, inflaming rivalries, and strengthening allegiances. Not only people and goods, but information traveled along these routes. When oddly clad strangers appeared offshore, the news would have spread like brushfire.  Giovanni da Verrazzano. Piermont Morgan Library. Giovanni da Verrazzano. Piermont Morgan Library. Five hundred years after Vikings first reached Newfoundland, Europeans became a regular presence in northern American waters. Basque, Portuguese, English, and French fishermen plied their trade off the coast of Canada, and there is evidence that they came into contact with Mi’kmak or Abenaki tribes in Maine as early as 1519. By the end of the century, a steady stream of European fisherman hunted whales and cod around Massachusetts Bay. They probably ventured ashore for fresh water and, perhaps, to trade with Native inhabitants. Official European exploration of New England began with an Italian working for France. In 1524, Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed west aboard La Dauphine in search of the fabled Northwest Passage. Upon reaching the lands of Siouan-speaking tribes (North Carolina), he kidnapped a boy to bring back to France and then turned north, hugging the coastline. He ventured into the areas of Mahican and Nahigansett (New York and Rhode Island), sailed past treacherous sandbanks and a “high promontory” that he named Pallavisino (Cape Cod), and proceeded to Wabanakhik (northern Maine), before ending his expedition in Beothuk territory (Newfoundland). Like many Renaissance voyagers, Verrazzano portrayed North America as a resource-rich idyll; present-day Rhode Island was “suitable for every kind of cultivation – grain, wine, or oil,” while Cape Cod “showed signs of minerals.” Notably, he described Natives’ varying attitudes towards the Europeans. Most, including the Narragansett, were “generous” and “gracious;” some were fearful; and the Abenaki were downright hostile: they insisted on trading “where the breakers were most violent,” attacked sailors who came ashore, and mooned Verrazzano’s crew upon its departure. Such behavior suggests that Maine tribes had a painful encounter with European fishermen even before La Dauphine arrived. Their neighbors to the south would soon have similar experiences. Exploration increased in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, spurred by stories of a northern El Dorado. Maps of the New World increasingly identified present-day Maine and southeastern Canada as the mythical Norumbega, a region of vast wealth that captured Europeans’ imaginations. In a possibly fictive and certainly fanciful travel account published in 1589, the sailor David Ingram claimed to have journeyed overland from Florida to Cape Breton and to have visited Bega, a city replete with “rubies six inches long,” pearls, and gold. The rumors lured Samuel de Champlain across the Atlantic in 1605. Though he discovered neither Norumbega nor the Northwest Passage, he did produce one of the earliest maps of Boston Harbor and an account of the people living there: “We saw in this place a great many little houses, which are situated in the fields where they sow their Indian corn. Furthermore in this bay there is a very broad river which we named the River Du Gas.” To the Massachuseuck, this river was the Quinobequin. To the Puritans, it would become the Charles. Europeans continued to frequent Massachusetts Bay in the years leading up to the founding of Plymouth Colony. Henry Hudson, John Smith, and Thomas Dermer all made the voyage, with disastrous consequences for Native peoples. In 1614, Smith’s associate Thomas Hunt kidnapped twenty-four members of the Patuxet tribe, including the renowned Tisquantum (Squanto), to sell as slaves in England. Hunt’s action upended the delicate trade relationship between the tribes and the English, initiating a period of open hostility. Indeed, local inhabitants might have stymied later colonization attempts if not for an invisible enemy that ravaged New England populations prior to 1620.

With the boatloads of Old World fishermen and explorers came an influx of Old World pathogens. Intermittent epidemics may have begun as early as the sixteenth century. Scholars debate which diseases swept through New England before the Pilgrims arrived; leptospirosis seems most plausible. One thing is clear, however: between 1616 and 1619, a plague decimated Native tribes. In 1619, Tisquantum returned home to a dead village. Scholars estimate that disease claimed the lives of 75-90% of eastern Massachusetts peoples over the course of the seventeenth century. The survivors were hard-pressed to repulse the thousands of colonists who poured into the region – and with whom the recorded history of Brighton and Worcester begins. |

AuthorArchitectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) is working to preserve and redevelop the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as a cutting-edge center for digital innovation. Archives

May 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed