|

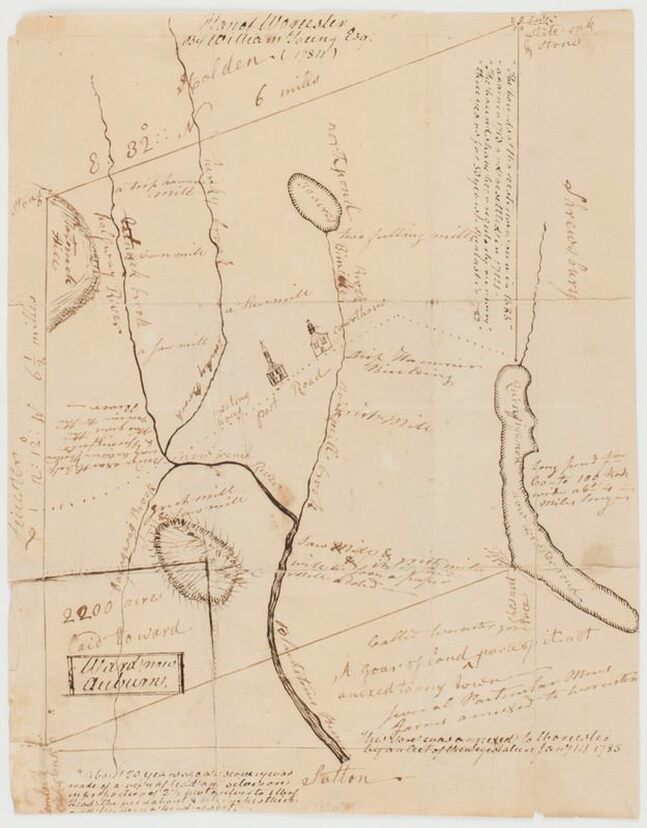

For this installment of "This Old Neighborhood," AHF decided to try something different: creating a map of Worcester shortly after this third and final establishment. We drew from a variety of eighteenth and nineteenth-century sources to reconstruct the town as it appeared in 1720. The map includes major roads, defensive garrisons, houses of worship, a burying ground, saw/grist mills, a tavern, and nineteen of the fifty-eight residences reported to have been built by that early point in the town's history. All locations are approximate.

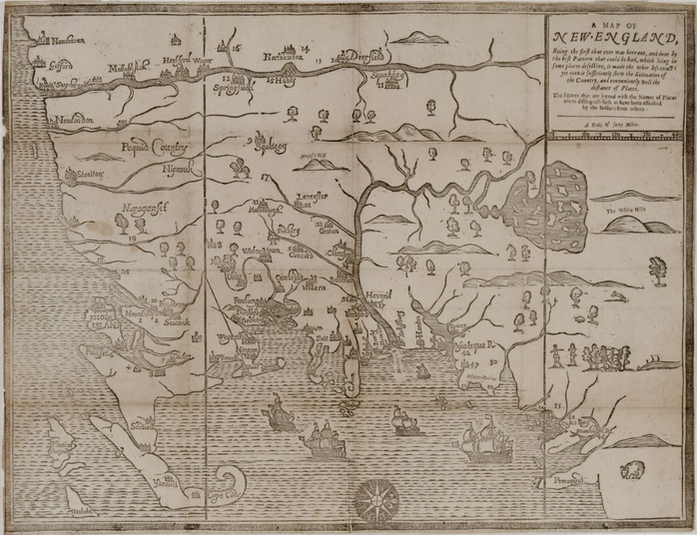

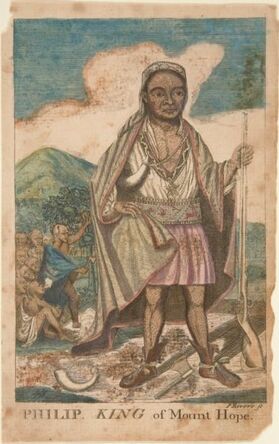

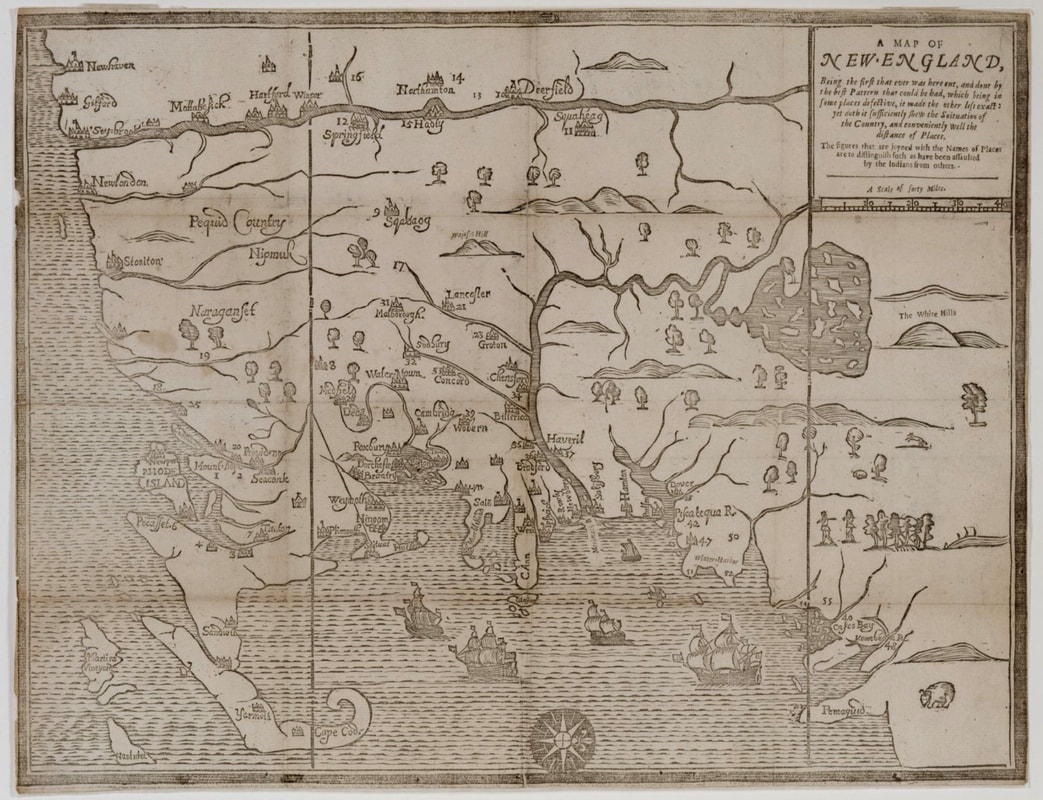

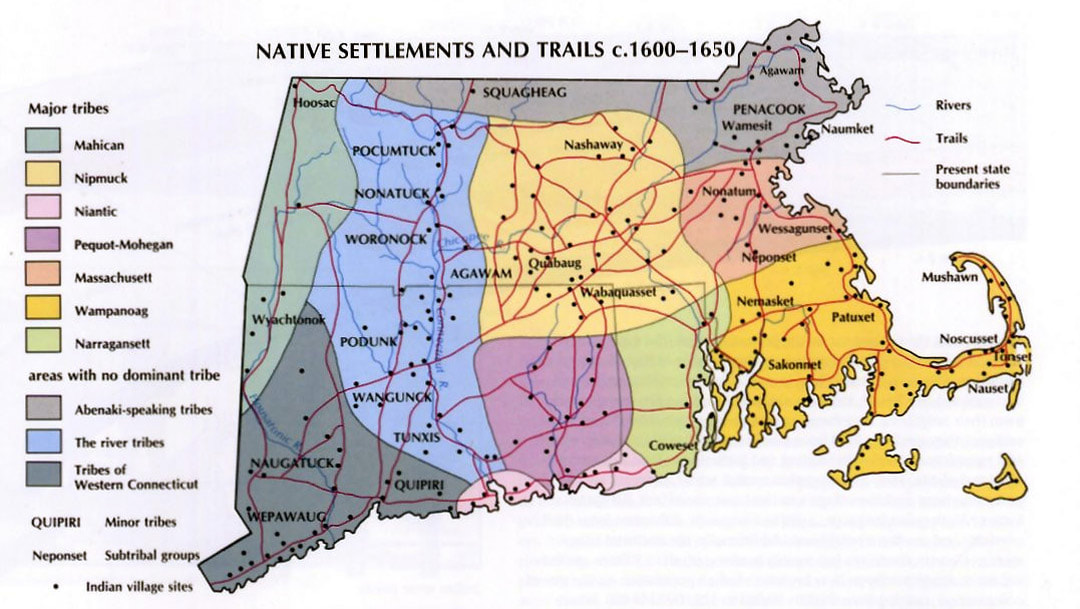

In 1720, Worcester's population is estimated to have numbered two hundred. The town was largely pastoral, yet already saw mills and grist mills - the beginnings of industry - were appearing along the many streams that coursed through the hilly terrain. A web of footpaths criss-crossed the meadows and forests, skirting beaver ponds, many following Nipmuc routes. Some had been widened into roads, which remain important thoroughfares in Worcester today: Main Street, Plantation Street, Pleasant Street, Burncoat Street... The town quickly expanded, growing more populous and prosperous by the year. How to use the map: Click the rectangular icon in the map's upper left corner to access the key, description, and sources. Clicking on the map's individual icons (e.g. houses, horses, etc.) will cause labels and descriptions of each feature to pop up. To zoom in and out, click the + and - symbols in the bottom left corner.  "A Map of New England," originally published in William Hubbard's "Narrative of the Troubles with the Indians," 1677. Massachusetts Historical Society. Oriented with the West at top, the map uses numbers to represent communities attacked by Native fighters - the number 17 (slightly left of center) denotes Quinsigamond Plantation. The city of Worcester got off to a rocky start. Quinsigamond Plantation, as it was called in 1675, was located in New England’s western frontier. Like other nearby colonial outposts, it had sprung up along the Boston Post Road to satisfy land-hungry colonists and expand Massachusetts territory, often at the expense of indigenous populations. The village had been purchased for a pittance from the local Nipmuc in 1674. Lots ranging in size from 25 to 100 acres had been laid out on “Indian broken up lands,” the settlers’ term for former Native agricultural areas. A two-story, wooden garrison house – the “old Indian Fort” – guarded the plantation and the approximately thirty Englishmen who called it home. Relations between the Quinsigamond Plantation settlers and the Nipmuc were initially calm, though colonial authorities tried to exert political influence over their Native neighbors. In September 1674, the Reverend John Eliot and Daniel Gookin visited the nearby village Pakachoag, where they were “kindly entertained” by sagamores Horowanninit (known to the English as Sagamore John) and Woosanakochu. Eliot and a Christianized Nipmuc minister, James Speen, preached and led a prayer service. A resident council then approved the two sagamores “to be rulers of this people and co-ordinate in power, clothed with the authority of the English government” and accepted Speen as their minister. It is unclear whether the villagers did so because they sought the colonial government’s protection or simply to humor their visitors. Whatever the case, the outbreak of King Philip’s War disrupted all efforts to forge tighter bonds between European authorities, Quinsigamond Plantation, and the Nipmuc.  Paul Revere's imaginative depiction of Metacomet, 1772. Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery. Paul Revere's imaginative depiction of Metacomet, 1772. Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery. Largely forgotten in public memory today, King Philip’s War was the bloodiest conflict in American history. What began as a Native rebellion against English colonization morphed into a war of extermination whereby the Wampanoag, Massachusett, Nipmuc, and Naragansett joined forces to oust the colonists from the region, and the English, with the help of Mahican, Pequot, and Praying Indian allies, fought back with equal or greater brutality. Between the war’s outbreak in June 1675 and its end in August 1676, up to forty percent of New England’s indigenous population had been killed, died in captivity, or sold into slavery. Five percent of colonists had perished and 67 English towns were destroyed, mostly on the frontier. Quinsigamond Plantation was among them. Hostilities erupted in the vicinity of Quinsigamond in June 1675, when the rebellion’s leader, the Wompanoag grand sachem Metacomet (also known as King Philip), forged an alliance with Horowanninit and the Nipmuc, and destroyed the colonial town of Quaboag (Brookfield). A month later, the constable of Pakachoag, Matoonas, attacked Mendon to avenge the execution of his son by the English in 1671. The region descended into violence. Companies of English soldiers indiscriminately ravaged the villages and crops of both enemy tribes and Praying Indians, and interned captive men, women, and children on the notorious Deer Island and Long Island in Boston Harbor. Meanwhile, Native fighters razed English settlements, among them Grafton and Marlborough. Tiny Quinsigamond Plantation was soon abandoned, and many of its initial settlers, including Ephraim Curtis, joined colonial forces against the rebelling tribes. The empty village was used occasionally as a military outpost until a band of Nipmuc burned it to the ground on December 2, 1675. Upon hearing the news, the fiery Puritan minister Increase Mather interpreted it as a sign of divine wrath. The violence raged through the winter and spring, when it became clear that the English were prevailing. Surviving Natives who were not enslaved or imprisoned gradually retreated from their ancestral homelands. Sensing defeat, Horowanninit of Pakachoag village and 180 followers abandoned their allegiance with Metacomet in July 1676 and entreated the colonial government in Boston for peace. As a sign of goodwill, they captured Matoonas, executed him on Boston Common, and impaled his head nearby, as his son’s had been five years earlier. Their gesture did little to gain the colonists’ trust: of the original 180 men, eleven were executed, thirty sold into slavery, and the rest imprisoned on Deer Island (which they soon escaped). When the war ended in August with Metacomet’s death, Horowanninit and his remaining followers returned to Pakachoag to find the region depopulated. Fewer than one thousand Nipmuc now inhabited what had once been a center of tribal life.

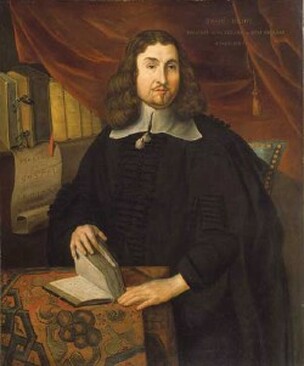

English settlers, too, returned to the area. Quinsigamond Plantation was rebuilt between 1678 and 1686 and renamed Worcester. Houses, mills, a church, a school, and a fort sprang up to replace the ones that had burned during the war, and colonial authorities allotted land to the settlers who moved in. However, the town’s renaissance was short-lived. Native unrest resurfaced in the 1690s, and the beginning of Queen Anne’s war in 1702 sounded the death-knell for the reestablished village. Horowanninit led his fellow Nipmuc in raids against Worcester, causing its residents to flee a second time. In 1713, the English made a third attempt to settle the area. This time, they succeeded. The town of Worcester grew into a thriving city whose diversity belied its bloody beginnings. And although colonial warfare devasted the Nipmuc, they were not exterminated. To this day, members of the Nipmuc Nation call Worcester and the surrounding region home.  Reverend John Eliot (alleged), artist unknown. National Portrait Gallery. Reverend John Eliot (alleged), artist unknown. National Portrait Gallery. How did eight acres of “very good chestnut tree land” become the second-largest city in New England? The answer begins with a colonial property dispute. By the mid-seventeenth century, Massachusetts Bay Colony was outgrowing itself. The towns dotting the coast – among them Salem, Boston, and Cambridge – swelled with thousands of Puritan migrants during the 1630s. Many of these settlers pushed west into Nipmuc territory, lured by vast tracts of seemingly unoccupied land that promised prosperity for their expanding families. New villages cropped up along the Boston Post Road (formerly the Old Connecticut Path): a “praying Indian” town called Natick, founded by “Apostle to the Indians” Reverend John Eliot; Framingham, an agricultural hamlet with a corn mill; and Sudbury, an ancient Native habitation dating back 12,000 years. Meanwhile, the growth of settlements along the Connecticut River created incentive to establish a town halfway between Boston and Springfield that would “unite and strengthen the inland plantations and…be advantageous for travellers.” It was only a matter of time before colonists crossed Lake Quinsigamond (“pickerel fishing place” in Algonquian) to the hilly frontier beyond. The earliest colonial proprietors in present-day Worcester were absentee landowners. Increase Nowell of Charlestown received the first land grant in 1657 – 3,200 acres of valuable meadowland at a time when the agricultural colony was still heavily forested. Another 1,000 acres of meadow were allotted to a church in Malden, and 500 acres to Thomas Noyes of Sudbury. However, it wasn’t until Thomas Noyes, together with three other colonists, acquired Increase Nowell’s property that there was any talk of establishing a “plantation” near Quinsigamond. In 1664, the four men successfully petitioned the colonial government to appoint a committee to survey the territory for a future village. Noyes even managed to get assigned to the task, before his untimely death threw a wrench in the plans. Only in 1668 was a commission finally dispatched to survey Quinsigamond. The committee, which included prominent colonist Daniel Gookin, issued a favorable report. They wrote that the region (present-day Worcester, Holden, and Auburn), though forested and somewhat swampy, contained “very good chestnut tree land” and was “well watered with ponds and brooks.” They also recommended dividing the territory into ninety house lots of 25 acres each, to be apportioned depending on “the quality, estate, usefulness, and other considerations of the person and family to whom they were granted,” and to reserve land for public necessities, including a training field, school, and commons. Unfortunately, nearly all the valuable meadowland was in private hands. The committee’s solution was to void the deeds and annex the land to the future Quinsigamond Plantation. There was just one problem: not every landowner cooperated. Ironically, it was the fate of Noyes’ Quinsigamond estate that delayed colonization of the Worcester area. When Noyes died, his widow sold two 250-acre tracts of meadow to a young man named Ephraim Curtis, also of Sudbury. One tract was in the center of the proposed plantation – precisely where the commission hoped to build a meeting house, minister’s residence, mill, and ten private dwellings. Curtis refused to give up the land and rejected all offers of compensation. He even constructed a house and trading post on his property along the Boston Post Road (now Main Street), a highly visible location that likely further aggravated the committee. For several years, the Massachusetts General Court resisted voiding the property rights of Worcester’s first English settler. The commission forged ahead anyway, enticing thirty men to establish homesteads at Quinsigamond Plantation in 1673. Curtis nevertheless remained a thorn in the commission’s side, and it continued to petition the General Court to settle the case once and for all. Finally, the Court acquiesced. Curtis was allowed to keep 50 acres of his original tract and to select another 250 from nearby house lots.

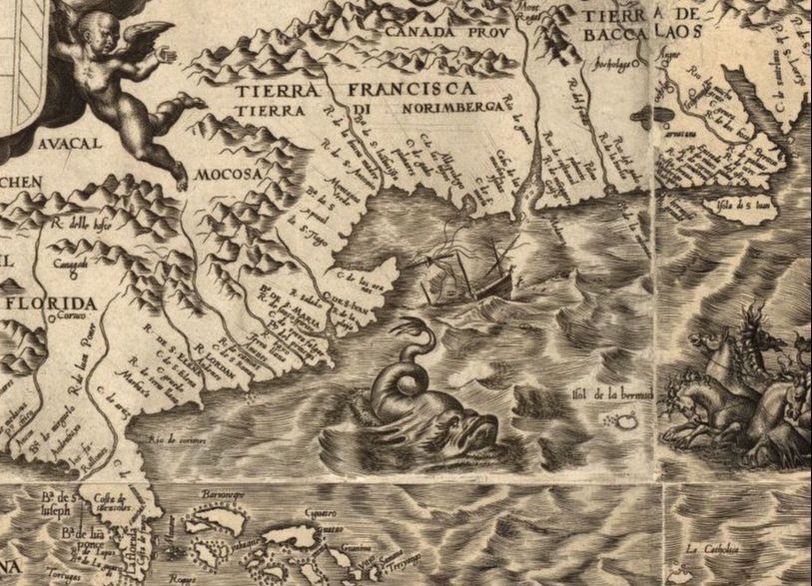

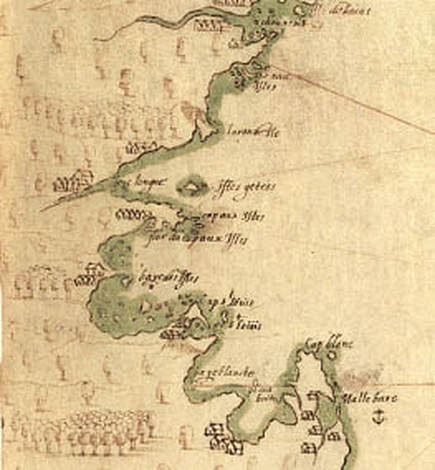

With the resolution of the land dispute, the committee turned its attention to the local Nipmuc who held the original claim to the territory. Three major Nipmuc villages occupied Pakachoag, Tataesset (now Tatnuck), and Wigwam Hills. Daniel Gookin spearheaded an effort to purchase the eight square miles of land from the tribe for Quinsigamond Plantation. In July 1674, he met with Hoorawannonit and Woonaskocha (respectively nicknamed Sagamore John and Sagamore Solomon), who agreed to a purchase price of twelve New England pounds, with a down payment of four yards of cloth and two coats – little more than $2,100 today. With a deed in hand and the Curtis case settled, the commission probably counted their venture a success. But their work was far from done. Tension between British settlers and Native tribes were rising throughout New England as the colonies continued to appropriate indigenous lands. Within two years of the commission’s triumph, Massachusetts would be embroiled in King Phillip’s War, and Quinsigamond caught in the crossfire. In popular memory, the modern history of Massachusetts began in 1620 with a group of English religious zealots. These men, women, and children are said to have ventured into an unknown region of the New World, a wilderness home to Native Americans who previously had never seen a European face. Massachusetts Bay, the story goes, was discovered, explored, and exploited by English dissidents. But popular memory often plays tricks. The Pilgrims encountered a region that was neither unmapped nor unaware of the wider world. Rather, it had played a role in the imperial Atlantic power struggle for decades. The coastal plains and rolling hills that would become so important in United States history were and remain home to many Algonquian-speaking tribes. Massachuseuck territory, named for the sacred Great Blue Hill (Massachusett, “Big Hill Place”), stretched across present-day Greater Boston. To the west lay Nippenet (“Freshwater Pond Place”), land of the Nipmuck. Their neighbors included the Wampanoag along the Cape; the Pocumtuck, Nonatuck, Woronock, and Agawam along the Connecticut River; the Muheconeok in the Berkshires; and the Penacook and Squagheag to the north. Dozens of long-distance trails connected villages throughout New England, facilitating trade, inflaming rivalries, and strengthening allegiances. Not only people and goods, but information traveled along these routes. When oddly clad strangers appeared offshore, the news would have spread like brushfire.  Giovanni da Verrazzano. Piermont Morgan Library. Giovanni da Verrazzano. Piermont Morgan Library. Five hundred years after Vikings first reached Newfoundland, Europeans became a regular presence in northern American waters. Basque, Portuguese, English, and French fishermen plied their trade off the coast of Canada, and there is evidence that they came into contact with Mi’kmak or Abenaki tribes in Maine as early as 1519. By the end of the century, a steady stream of European fisherman hunted whales and cod around Massachusetts Bay. They probably ventured ashore for fresh water and, perhaps, to trade with Native inhabitants. Official European exploration of New England began with an Italian working for France. In 1524, Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed west aboard La Dauphine in search of the fabled Northwest Passage. Upon reaching the lands of Siouan-speaking tribes (North Carolina), he kidnapped a boy to bring back to France and then turned north, hugging the coastline. He ventured into the areas of Mahican and Nahigansett (New York and Rhode Island), sailed past treacherous sandbanks and a “high promontory” that he named Pallavisino (Cape Cod), and proceeded to Wabanakhik (northern Maine), before ending his expedition in Beothuk territory (Newfoundland). Like many Renaissance voyagers, Verrazzano portrayed North America as a resource-rich idyll; present-day Rhode Island was “suitable for every kind of cultivation – grain, wine, or oil,” while Cape Cod “showed signs of minerals.” Notably, he described Natives’ varying attitudes towards the Europeans. Most, including the Narragansett, were “generous” and “gracious;” some were fearful; and the Abenaki were downright hostile: they insisted on trading “where the breakers were most violent,” attacked sailors who came ashore, and mooned Verrazzano’s crew upon its departure. Such behavior suggests that Maine tribes had a painful encounter with European fishermen even before La Dauphine arrived. Their neighbors to the south would soon have similar experiences. Exploration increased in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, spurred by stories of a northern El Dorado. Maps of the New World increasingly identified present-day Maine and southeastern Canada as the mythical Norumbega, a region of vast wealth that captured Europeans’ imaginations. In a possibly fictive and certainly fanciful travel account published in 1589, the sailor David Ingram claimed to have journeyed overland from Florida to Cape Breton and to have visited Bega, a city replete with “rubies six inches long,” pearls, and gold. The rumors lured Samuel de Champlain across the Atlantic in 1605. Though he discovered neither Norumbega nor the Northwest Passage, he did produce one of the earliest maps of Boston Harbor and an account of the people living there: “We saw in this place a great many little houses, which are situated in the fields where they sow their Indian corn. Furthermore in this bay there is a very broad river which we named the River Du Gas.” To the Massachuseuck, this river was the Quinobequin. To the Puritans, it would become the Charles. Europeans continued to frequent Massachusetts Bay in the years leading up to the founding of Plymouth Colony. Henry Hudson, John Smith, and Thomas Dermer all made the voyage, with disastrous consequences for Native peoples. In 1614, Smith’s associate Thomas Hunt kidnapped twenty-four members of the Patuxet tribe, including the renowned Tisquantum (Squanto), to sell as slaves in England. Hunt’s action upended the delicate trade relationship between the tribes and the English, initiating a period of open hostility. Indeed, local inhabitants might have stymied later colonization attempts if not for an invisible enemy that ravaged New England populations prior to 1620.

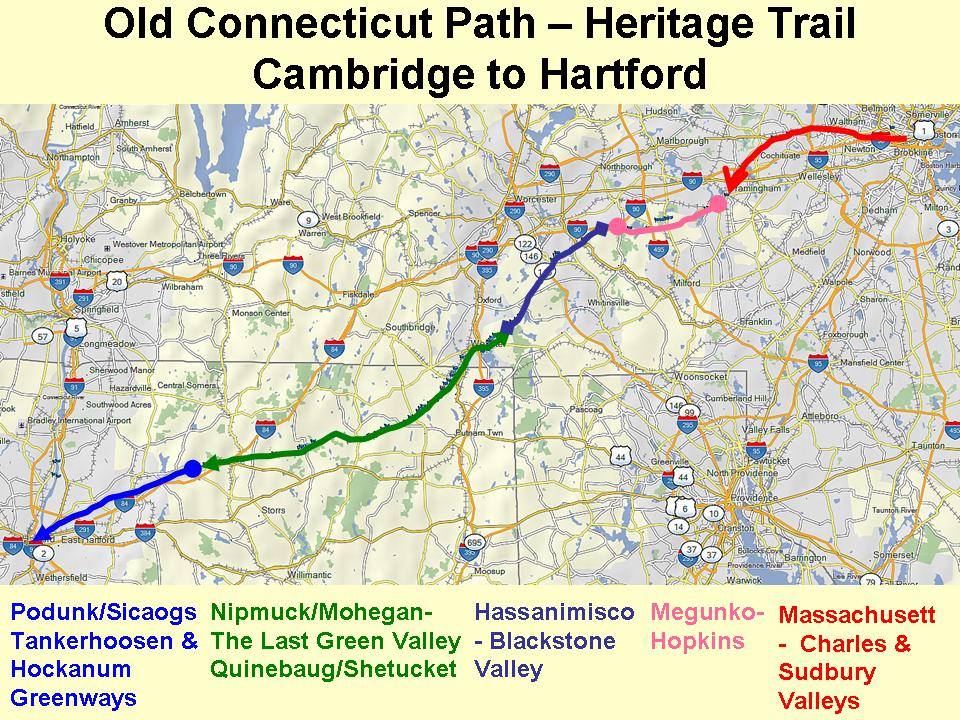

With the boatloads of Old World fishermen and explorers came an influx of Old World pathogens. Intermittent epidemics may have begun as early as the sixteenth century. Scholars debate which diseases swept through New England before the Pilgrims arrived; leptospirosis seems most plausible. One thing is clear, however: between 1616 and 1619, a plague decimated Native tribes. In 1619, Tisquantum returned home to a dead village. Scholars estimate that disease claimed the lives of 75-90% of eastern Massachusetts peoples over the course of the seventeenth century. The survivors were hard-pressed to repulse the thousands of colonists who poured into the region – and with whom the recorded history of Brighton and Worcester begins. When English colonists arrived on the shores of Massachusetts four hundred years ago, they beheld an unfamiliar territory almost devoid of features that might have reminded them of home. There were no carriage paths or cattle pastures, no rooting hogs or crowing roosters, no church steeples or tolling bells. Steep drumlins loomed above the coast, beyond which forests and marshland stretched westward. Mountain lions skulked behind boulders. Wolves howled at night. To settlers accustomed to a treeless countryside subdued beneath the plow, New England was a “vacant wilderness…a place not inhabited but by the barbarous nations.” Little did they understand the way of life that those nations had created over the past three thousand years. Massachusetts during the Woodland Period (3,000-400 BP) was not a pristine wilderness, but an increasingly manipulated landscape home to tens of thousands of Native Americans. As post-glacial sea levels stabilized, Woodland peoples adopted new patterns of habitation and movement that spurred agricultural, technological, and cultural development. Many gravitated toward coastal areas and established long-term seasonal settlements, where they began to plant crops. Initially, they selectively bred weedy vegetation including sunflower, goosefoot, and sumpweed, and boiled the seeds in porridges. By 1000 CE, Central American cultivars – maize, squash, and beans – had arrived in New England and were becoming increasingly important in local diets. Woodland peoples’ migratory lifestyles enabled them to diversify their food sources. Archeological evidence, such as shell middens (ancient trash heaps) on Spectacle Island, suggests that Native Americans settled in large villages during the spring and fall, where they planted and harvested crops, fished, clammed, and hunted, and held political meetings (indeed, in 1614, explorer and colonist John Smith recorded that Native peoples grew maize on the Harbor Islands). During the summer and winter, many villages disbanded. Residents moved to smaller settlements in the region to better exploit food sources while crops ripened or the ground lay frozen. Agriculture transformed the Massachusetts landscape. Though the area remained heavily forested at the time of European contact, patches of cleared ground reflected repeated seasonal use. Native Americans believed that they owned the use of land, rather than the land itself; instead of adopting permanent farming sites, they tilled soil until it was no longer fertile (about eight to ten years) and then relocated. Women cleared new land by setting fires at the base of trees to kill them, and, once the dead wood fell, by burning it away. This method, along with the practice of burning fires all night during both the winter and summer, meant that localized deforestation was common. Thousands of acres near Boston were treeless by 1630; elsewhere, the whitened trunks of girdled trees surveyed cornstalks intertwined with bean and squash vines. Far from a “vacant wilderness,” Massachusetts was an intensively used homeland. Fire enabled local tribes not only to grow crops and stay warm, but also to hunt, gather, and travel. English colonists were astounded that Woodland peoples set large ground fires in the forests during the spring and fall, and were equally impressed with the effects. The woods near Native villages tended to be clear of tangled undergrowth. The widely spaced trees, grass, and pioneering berry bushes created a park-like setting that attracted game, facilitated hunting, and limited the risk of future fires burning out of control. The relative openness of Woodland Period forests also eased long-distance travel. Overland routes developed over thousands of years, crisscrossing tribal territories. Among the most famous was the Old Connecticut Path: it began near present-day Cambridge, following the Quinobequin ("meandering," later Charles) River through Massachusett territory before curving southwest into Nipmuck land. From there, it passed south of present-day Worcester and continued on to the area along the Connecticut River that would eventually become Hartford. (Parts of the route remain heavily traveled today – the Old Connecticut Path is now known as MA Route 9 and MA Route 126.) Europeans arriving in New England did not have to build everything from scratch. They entered a region that already had the equivalent of an international highway system, which they used to expand their settlements. At the dawn of the seventeenth century, modern Native tribes were well-established in Massachusetts. They occupied defined homelands and engineered the environment to facilitate a migratory lifestyle that maximized the yield of local resources. They were also increasingly aware of the world beyond the Atlantic – a world that appeared on the horizon as billowing ship sails, dropped anchor and fishing lines in Massachusetts Bay, and, until 1620, never stayed for long.

Eighteen thousand years ago, Worcester was smothered beneath 1,800 feet of ice. The blue-white wasteland extended in all directions, burying Mount Wachusett and slowly scouring away the soft sedimentary rock of more recent eons from ancient, underlying schists. Locked in an ice sheet that stretched from the Arctic to present-day New Jersey, Worcester County was unrecognizable: a crevassed expanse of silence reaching toward the rising sun and tumbling into Atlantic waters that were hundreds of feet lower than they are today. The Laurentide ice age was the culmination of one million years of glaciations that dramatically altered the New England landscape. Fluctuating temperatures during the Pleistocene resulted in glaciers repeatedly advancing and retreating across the region. The most recent major ice age – which, according to geologists, is still occurring – began 25,000 years Before Present (BP). Long winters and cool summers caused more snow to fall than melt. The snow eventually compacted under its own weight into an ice sheet that left a rugged legacy in Massachusetts. As the glaciers moved, they accumulated silt, gravel, and even boulders; water seeped into cracks in the bedrock, froze, and expanded, breaking off large chunks of stone that were carried away by the ice. When the ice began to melt around 17,500 BP, it deposited these sediments unevenly throughout the landscape. Leisurely hikes in Worcester County often reveal glacial features: Dexter Drumlin, Purgatory Chasm, eskers in Worcester’s Hadwen Park, erratics in Holbrook Forest, and innumerable wetlands, often the result of poor drainage in areas of tightly packed glacial till. Gradually the ice sheet receded from the region. By 14,000 BP, the barren earth was once again exposed to the sky. Another thousand years would pass before humans braved the tundra of Massachusetts. Archaeological evidence suggests that Paleo-Indians initially settled near major rivers and bodies of water. In 2015, an amateur archaeologist unearthed a small, triangular piece of flint in a Northampton potato field. He recognized it as a what it was right away – a Clovis point arrowhead. Researchers soon confirmed that the arrowhead was 12,800 years old, one of the oldest artifacts ever discovered in the state. Other archaeological sites in Western Massachusetts indicate that Paleo-Indians used the lush Connecticut River Valley as a seasonal hunting ground. Although similar prehistoric evidence is scarcer in Worcester County, fluted points have been found in the Chicopee and Blackstone River Drainages. Local Paleo-Indians likely lived in small, migratory bands, hunting mastodon as well as smaller game and fishing in the region’s many streams and ponds. They adapted to a warming climate that turned the tundra into a vast boreal forest, which, in turn, gave way to hardwoods. By 9,500 BP, ecological change and over-hunting had eradicated the megafauna and created a landscape that would shape humans’ lives for the next nine millennia. Worcester County became more densely populated during the Archaic Period (9,000-3,000 BP). Human settlement spread to present-day West Brookfield, Westborough, and other areas, where archaeologists have discovered projectile points, stone tools, and burial sites. Like their ancestors, Archaic peoples were predominantly hunter-gatherers. They travelled between seasonal hunting grounds in pursuit of game and were deeply familiar with the movements of birds and fish. They mined quartzite from local quarries to fashion weapons and tools, littering the ground with stone flakes that enable today’s archaeologists to identify sites of habitation (such as the Cracked Rock rockshelter in Millbury). Throughout this period, Archaic cultures evolved. The ancient residents of Worcester County adopted new styles of stone and bone craftsmanship as technology improved and fashions changed. They also came to depend more heavily on plant foods, giving rise to the development of local agriculture 3,000 years ago. This milestone was one of many that marked the transition from the Archaic era to the Woodland Period (3,000-450 BP). The millennia preceding European colonization would witness the genesis of contemporary Native American tribes and of the vibrant civilizations that greeted English settlers on the shores of the New World.

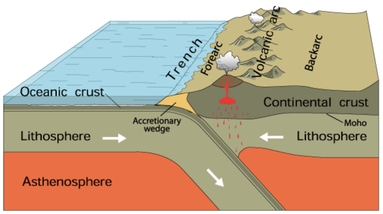

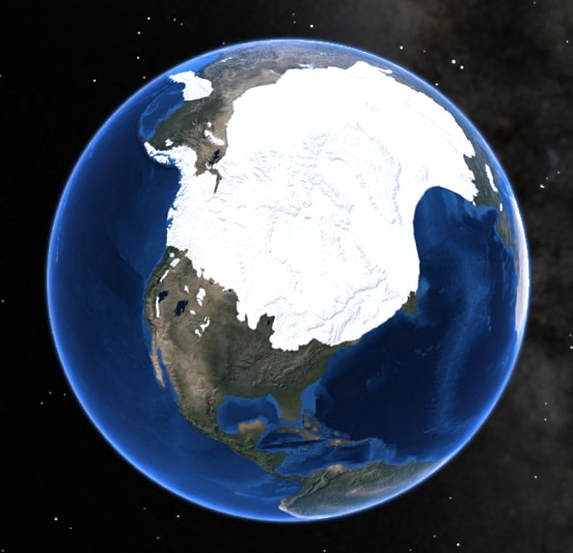

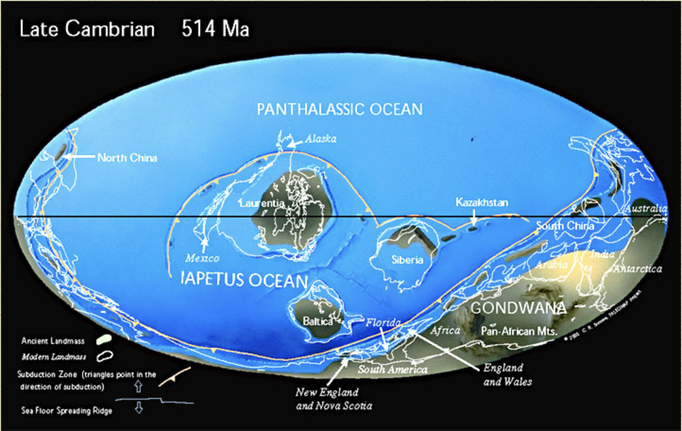

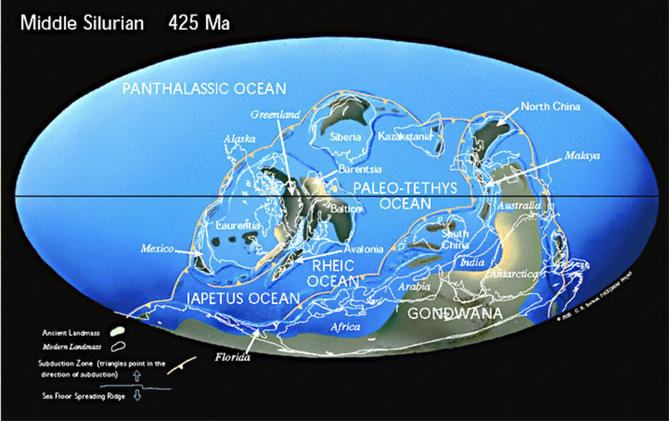

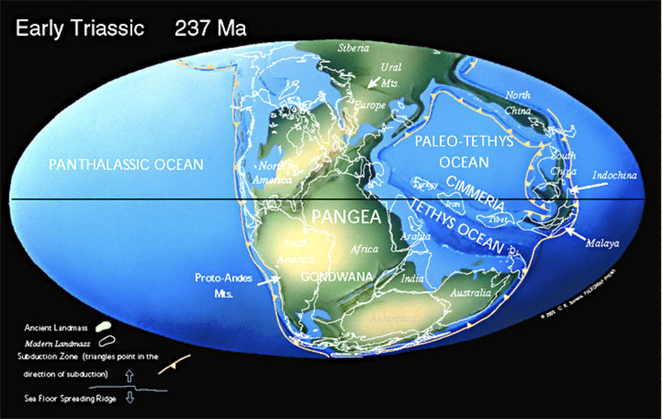

Subduction. Courtesy of USGS. Subduction. Courtesy of USGS. Imagine a world where South America is at the South Pole, Siberia, along the Tropic of Capricorn, and Greenland, at the Equator. In this world, Florida is a frigid strip of coast connecting South America and Africa. Canada bakes beneath a bright equatorial sun. The rest of North America is a scuba-diver's paradise – assuming scuba-divers numbered among the primitive, single-cell organisms that existed 550 million years ago. Welcome to the Late Precambrian, an era of dramatic geological change and the beginning of New England’s story. At this point, the earth was 3.5 billion years old. It had already experienced multiple episodes of continental drift, volcanism, and glaciation. The Grenville Mountain chain, formed during an earlier period of tectonic collision, had eroded. All that remained was a small layer of bedrock and a large amount of sediment that would eventually become western Massachusetts. Three major continents contained most of the planet’s land mass: Laurentia, Baltica, and the supercontinent Gondwana, whose coastline roiled with volcanic activity. The earthquakes and lava flows were symptoms of tectonic subduction (when one tectonic plate dives beneath another) and rifting (when two plates diverge). Over time, these subterranean stirrings formed the Avalon mountain range and Boston Rift Basin off the coast of present-day South America. We now call this region New England. As Earth entered the Cambrian Period, Avalon broke away from Gondwana. Sediments filled the rift basin and compressed into the Cambridge Argillite and Roxbury Conglomerate (puddingstone) rock formations underlying Greater Boston today. Between 430 and 390 million years ago, Avalon collided with Laurentia, forming the Northern Appalachians. This period of tectonic uplift coincided with rising oxygen levels and an explosion of multicellular life. Complex organisms spread across the globe as New England rose from the depths of the ocean. Over the succeeding eons, the planet’s crust continued to transform. The continents collided again 250 million years ago to form Pangaea, lifting the Appalachians to Himalayan heights, and then separated fifty million years later. This period of rifting created today’s continents and instigated more lava flows. We can still see evidence of this geological turbulence in the igneous and metamorphic rocks of Worcester County. Volcanic activity subsided as the continents drifted to their present locations. Massachusetts was thereafter shaped by deposition, weathering, and erosion. Temperatures rose, fell, and rose again, causing frequent glaciations that carved the Northeastern bedrock. Meanwhile, life evolved. The region was alternately submerged in shallow seas teeming with crustaceans and fish, and raised high and dry, a coastal forest where dinosaurs roamed. By the time Homo sapiens arrived in New England twelve thousand years ago, the region was a frozen tundra. The latest Ice Age scarred the landscape with eskers, dimpled it with kettle ponds, and pimpled it with erratics – a rugged topography that determined where humans settled, and upon which they would eventually unleash their transformative might.

|

AuthorArchitectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) is working to preserve and redevelop the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as a cutting-edge center for digital innovation. Archives

May 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed