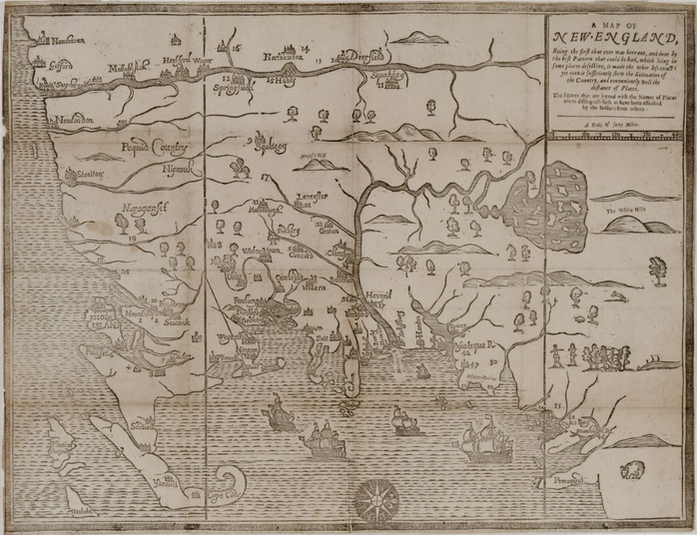

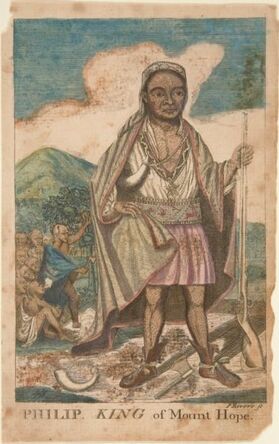

"A Map of New England," originally published in William Hubbard's "Narrative of the Troubles with the Indians," 1677. Massachusetts Historical Society. Oriented with the West at top, the map uses numbers to represent communities attacked by Native fighters - the number 17 (slightly left of center) denotes Quinsigamond Plantation. The city of Worcester got off to a rocky start. Quinsigamond Plantation, as it was called in 1675, was located in New England’s western frontier. Like other nearby colonial outposts, it had sprung up along the Boston Post Road to satisfy land-hungry colonists and expand Massachusetts territory, often at the expense of indigenous populations. The village had been purchased for a pittance from the local Nipmuc in 1674. Lots ranging in size from 25 to 100 acres had been laid out on “Indian broken up lands,” the settlers’ term for former Native agricultural areas. A two-story, wooden garrison house – the “old Indian Fort” – guarded the plantation and the approximately thirty Englishmen who called it home. Relations between the Quinsigamond Plantation settlers and the Nipmuc were initially calm, though colonial authorities tried to exert political influence over their Native neighbors. In September 1674, the Reverend John Eliot and Daniel Gookin visited the nearby village Pakachoag, where they were “kindly entertained” by sagamores Horowanninit (known to the English as Sagamore John) and Woosanakochu. Eliot and a Christianized Nipmuc minister, James Speen, preached and led a prayer service. A resident council then approved the two sagamores “to be rulers of this people and co-ordinate in power, clothed with the authority of the English government” and accepted Speen as their minister. It is unclear whether the villagers did so because they sought the colonial government’s protection or simply to humor their visitors. Whatever the case, the outbreak of King Philip’s War disrupted all efforts to forge tighter bonds between European authorities, Quinsigamond Plantation, and the Nipmuc.  Paul Revere's imaginative depiction of Metacomet, 1772. Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery. Paul Revere's imaginative depiction of Metacomet, 1772. Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery. Largely forgotten in public memory today, King Philip’s War was the bloodiest conflict in American history. What began as a Native rebellion against English colonization morphed into a war of extermination whereby the Wampanoag, Massachusett, Nipmuc, and Naragansett joined forces to oust the colonists from the region, and the English, with the help of Mahican, Pequot, and Praying Indian allies, fought back with equal or greater brutality. Between the war’s outbreak in June 1675 and its end in August 1676, up to forty percent of New England’s indigenous population had been killed, died in captivity, or sold into slavery. Five percent of colonists had perished and 67 English towns were destroyed, mostly on the frontier. Quinsigamond Plantation was among them. Hostilities erupted in the vicinity of Quinsigamond in June 1675, when the rebellion’s leader, the Wompanoag grand sachem Metacomet (also known as King Philip), forged an alliance with Horowanninit and the Nipmuc, and destroyed the colonial town of Quaboag (Brookfield). A month later, the constable of Pakachoag, Matoonas, attacked Mendon to avenge the execution of his son by the English in 1671. The region descended into violence. Companies of English soldiers indiscriminately ravaged the villages and crops of both enemy tribes and Praying Indians, and interned captive men, women, and children on the notorious Deer Island and Long Island in Boston Harbor. Meanwhile, Native fighters razed English settlements, among them Grafton and Marlborough. Tiny Quinsigamond Plantation was soon abandoned, and many of its initial settlers, including Ephraim Curtis, joined colonial forces against the rebelling tribes. The empty village was used occasionally as a military outpost until a band of Nipmuc burned it to the ground on December 2, 1675. Upon hearing the news, the fiery Puritan minister Increase Mather interpreted it as a sign of divine wrath. The violence raged through the winter and spring, when it became clear that the English were prevailing. Surviving Natives who were not enslaved or imprisoned gradually retreated from their ancestral homelands. Sensing defeat, Horowanninit of Pakachoag village and 180 followers abandoned their allegiance with Metacomet in July 1676 and entreated the colonial government in Boston for peace. As a sign of goodwill, they captured Matoonas, executed him on Boston Common, and impaled his head nearby, as his son’s had been five years earlier. Their gesture did little to gain the colonists’ trust: of the original 180 men, eleven were executed, thirty sold into slavery, and the rest imprisoned on Deer Island (which they soon escaped). When the war ended in August with Metacomet’s death, Horowanninit and his remaining followers returned to Pakachoag to find the region depopulated. Fewer than one thousand Nipmuc now inhabited what had once been a center of tribal life.

English settlers, too, returned to the area. Quinsigamond Plantation was rebuilt between 1678 and 1686 and renamed Worcester. Houses, mills, a church, a school, and a fort sprang up to replace the ones that had burned during the war, and colonial authorities allotted land to the settlers who moved in. However, the town’s renaissance was short-lived. Native unrest resurfaced in the 1690s, and the beginning of Queen Anne’s war in 1702 sounded the death-knell for the reestablished village. Horowanninit led his fellow Nipmuc in raids against Worcester, causing its residents to flee a second time. In 1713, the English made a third attempt to settle the area. This time, they succeeded. The town of Worcester grew into a thriving city whose diversity belied its bloody beginnings. And although colonial warfare devasted the Nipmuc, they were not exterminated. To this day, members of the Nipmuc Nation call Worcester and the surrounding region home.

Yulya Sevelova

6/20/2021 03:04:29 pm

To find out that America had concentration camps was a major shock and disappointment, as in realizing that the U.S. hid a lot of important facts from the world. And that barely 50 years from them landing at Plymouth Rock, those same people rewarded the Native hosts who saved them from certain death, and allowed the Pilgrims and Puritans to have sanctuary here, were in fact invaded by those English. And then taken in chains to Deer Island during King Philip's War, to die in exile, basically. This wasn't covered in the history books I read growing up ! How creepy all this is ! I'm sorry, but the more I find out about the U.S., I wish we'd gone to a third country, instead of this one . Not many safe countries in the world to move to. This, alongside more things coming to light, should be taught in history books during citizenship classes !! People have the right to know what they're getting into by immigrating here.

Gina T

1/2/2024 09:52:57 pm

Do not rely on American History books made by the curriculum to tell you the truth. 1619 … ring a bell? What did they tell us about the beginning of the “establishment” of this country ..?? It’s all b s 11/30/2022 07:55:54 pm

Thank you for remembering a colonists-provoked war that ministers sanctioned in the name of their God. This was a tiny fraction of inhumanity that continues by current law makers to deny status of nationality to surviving tribes. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorArchitectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) is working to preserve and redevelop the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as a cutting-edge center for digital innovation. Archives

May 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed