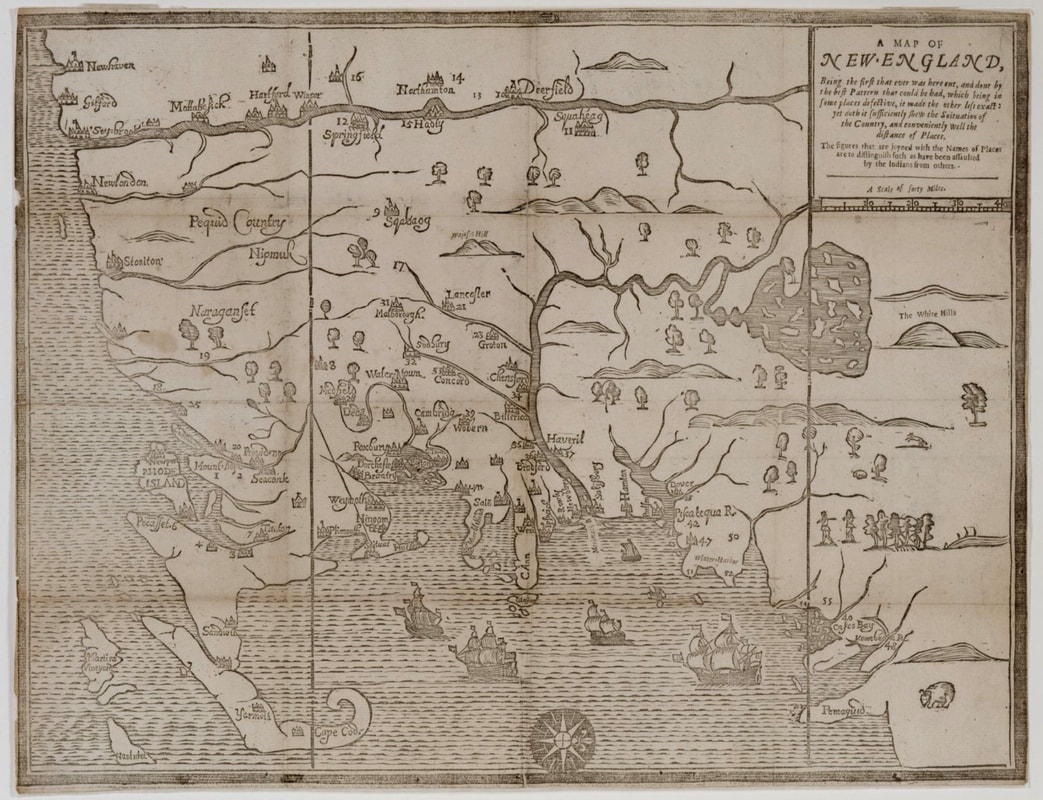

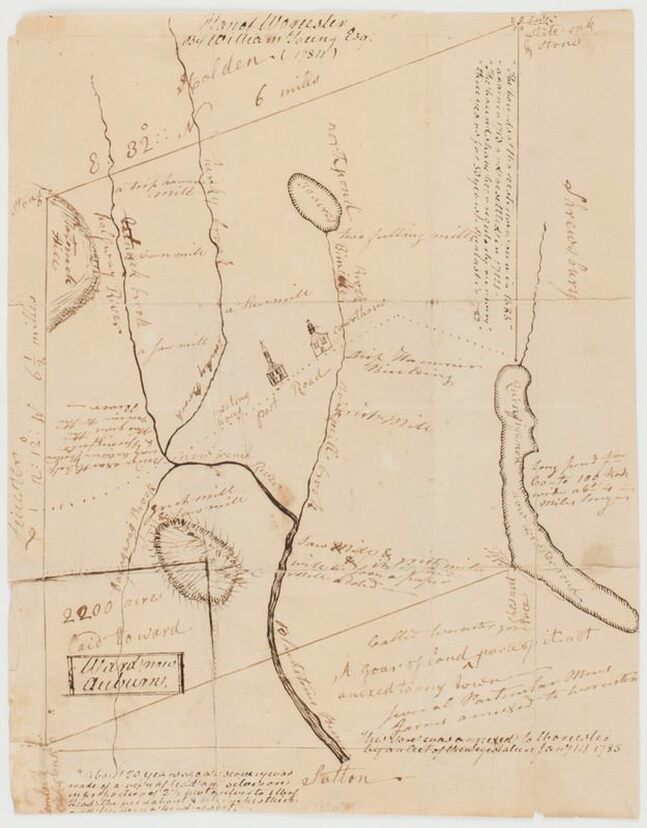

Reverend John Eliot (alleged), artist unknown. National Portrait Gallery. Reverend John Eliot (alleged), artist unknown. National Portrait Gallery. How did eight acres of “very good chestnut tree land” become the second-largest city in New England? The answer begins with a colonial property dispute. By the mid-seventeenth century, Massachusetts Bay Colony was outgrowing itself. The towns dotting the coast – among them Salem, Boston, and Cambridge – swelled with thousands of Puritan migrants during the 1630s. Many of these settlers pushed west into Nipmuc territory, lured by vast tracts of seemingly unoccupied land that promised prosperity for their expanding families. New villages cropped up along the Boston Post Road (formerly the Old Connecticut Path): a “praying Indian” town called Natick, founded by “Apostle to the Indians” Reverend John Eliot; Framingham, an agricultural hamlet with a corn mill; and Sudbury, an ancient Native habitation dating back 12,000 years. Meanwhile, the growth of settlements along the Connecticut River created incentive to establish a town halfway between Boston and Springfield that would “unite and strengthen the inland plantations and…be advantageous for travellers.” It was only a matter of time before colonists crossed Lake Quinsigamond (“pickerel fishing place” in Algonquian) to the hilly frontier beyond. The earliest colonial proprietors in present-day Worcester were absentee landowners. Increase Nowell of Charlestown received the first land grant in 1657 – 3,200 acres of valuable meadowland at a time when the agricultural colony was still heavily forested. Another 1,000 acres of meadow were allotted to a church in Malden, and 500 acres to Thomas Noyes of Sudbury. However, it wasn’t until Thomas Noyes, together with three other colonists, acquired Increase Nowell’s property that there was any talk of establishing a “plantation” near Quinsigamond. In 1664, the four men successfully petitioned the colonial government to appoint a committee to survey the territory for a future village. Noyes even managed to get assigned to the task, before his untimely death threw a wrench in the plans. Only in 1668 was a commission finally dispatched to survey Quinsigamond. The committee, which included prominent colonist Daniel Gookin, issued a favorable report. They wrote that the region (present-day Worcester, Holden, and Auburn), though forested and somewhat swampy, contained “very good chestnut tree land” and was “well watered with ponds and brooks.” They also recommended dividing the territory into ninety house lots of 25 acres each, to be apportioned depending on “the quality, estate, usefulness, and other considerations of the person and family to whom they were granted,” and to reserve land for public necessities, including a training field, school, and commons. Unfortunately, nearly all the valuable meadowland was in private hands. The committee’s solution was to void the deeds and annex the land to the future Quinsigamond Plantation. There was just one problem: not every landowner cooperated. Ironically, it was the fate of Noyes’ Quinsigamond estate that delayed colonization of the Worcester area. When Noyes died, his widow sold two 250-acre tracts of meadow to a young man named Ephraim Curtis, also of Sudbury. One tract was in the center of the proposed plantation – precisely where the commission hoped to build a meeting house, minister’s residence, mill, and ten private dwellings. Curtis refused to give up the land and rejected all offers of compensation. He even constructed a house and trading post on his property along the Boston Post Road (now Main Street), a highly visible location that likely further aggravated the committee. For several years, the Massachusetts General Court resisted voiding the property rights of Worcester’s first English settler. The commission forged ahead anyway, enticing thirty men to establish homesteads at Quinsigamond Plantation in 1673. Curtis nevertheless remained a thorn in the commission’s side, and it continued to petition the General Court to settle the case once and for all. Finally, the Court acquiesced. Curtis was allowed to keep 50 acres of his original tract and to select another 250 from nearby house lots.

With the resolution of the land dispute, the committee turned its attention to the local Nipmuc who held the original claim to the territory. Three major Nipmuc villages occupied Pakachoag, Tataesset (now Tatnuck), and Wigwam Hills. Daniel Gookin spearheaded an effort to purchase the eight square miles of land from the tribe for Quinsigamond Plantation. In July 1674, he met with Hoorawannonit and Woonaskocha (respectively nicknamed Sagamore John and Sagamore Solomon), who agreed to a purchase price of twelve New England pounds, with a down payment of four yards of cloth and two coats – little more than $2,100 today. With a deed in hand and the Curtis case settled, the commission probably counted their venture a success. But their work was far from done. Tension between British settlers and Native tribes were rising throughout New England as the colonies continued to appropriate indigenous lands. Within two years of the commission’s triumph, Massachusetts would be embroiled in King Phillip’s War, and Quinsigamond caught in the crossfire. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorArchitectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) is working to preserve and redevelop the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as a cutting-edge center for digital innovation. Archives

May 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed