|

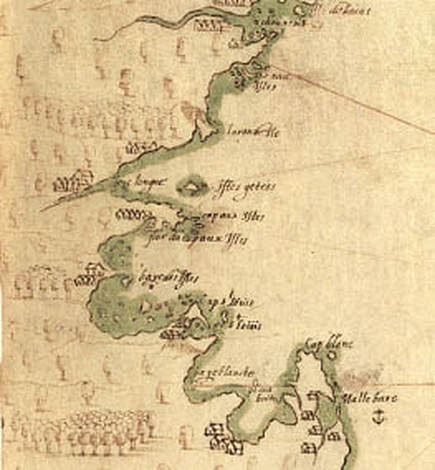

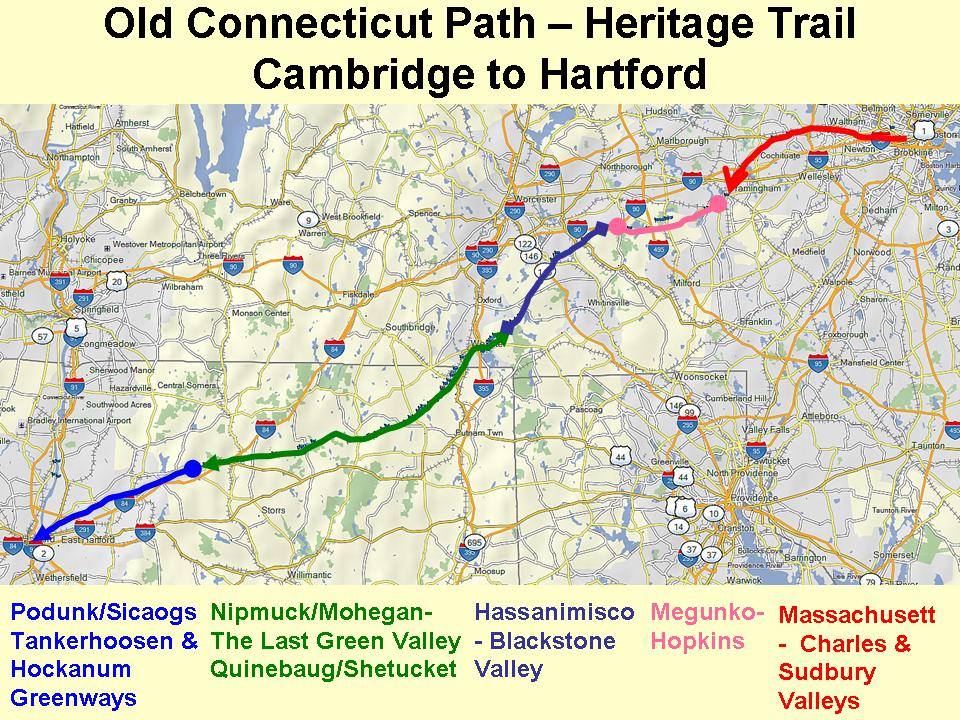

When English colonists arrived on the shores of Massachusetts four hundred years ago, they beheld an unfamiliar territory almost devoid of features that might have reminded them of home. There were no carriage paths or cattle pastures, no rooting hogs or crowing roosters, no church steeples or tolling bells. Steep drumlins loomed above the coast, beyond which forests and marshland stretched westward. Mountain lions skulked behind boulders. Wolves howled at night. To settlers accustomed to a treeless countryside subdued beneath the plow, New England was a “vacant wilderness…a place not inhabited but by the barbarous nations.” Little did they understand the way of life that those nations had created over the past three thousand years. Massachusetts during the Woodland Period (3,000-400 BP) was not a pristine wilderness, but an increasingly manipulated landscape home to tens of thousands of Native Americans. As post-glacial sea levels stabilized, Woodland peoples adopted new patterns of habitation and movement that spurred agricultural, technological, and cultural development. Many gravitated toward coastal areas and established long-term seasonal settlements, where they began to plant crops. Initially, they selectively bred weedy vegetation including sunflower, goosefoot, and sumpweed, and boiled the seeds in porridges. By 1000 CE, Central American cultivars – maize, squash, and beans – had arrived in New England and were becoming increasingly important in local diets. Woodland peoples’ migratory lifestyles enabled them to diversify their food sources. Archeological evidence, such as shell middens (ancient trash heaps) on Spectacle Island, suggests that Native Americans settled in large villages during the spring and fall, where they planted and harvested crops, fished, clammed, and hunted, and held political meetings (indeed, in 1614, explorer and colonist John Smith recorded that Native peoples grew maize on the Harbor Islands). During the summer and winter, many villages disbanded. Residents moved to smaller settlements in the region to better exploit food sources while crops ripened or the ground lay frozen. Agriculture transformed the Massachusetts landscape. Though the area remained heavily forested at the time of European contact, patches of cleared ground reflected repeated seasonal use. Native Americans believed that they owned the use of land, rather than the land itself; instead of adopting permanent farming sites, they tilled soil until it was no longer fertile (about eight to ten years) and then relocated. Women cleared new land by setting fires at the base of trees to kill them, and, once the dead wood fell, by burning it away. This method, along with the practice of burning fires all night during both the winter and summer, meant that localized deforestation was common. Thousands of acres near Boston were treeless by 1630; elsewhere, the whitened trunks of girdled trees surveyed cornstalks intertwined with bean and squash vines. Far from a “vacant wilderness,” Massachusetts was an intensively used homeland. Fire enabled local tribes not only to grow crops and stay warm, but also to hunt, gather, and travel. English colonists were astounded that Woodland peoples set large ground fires in the forests during the spring and fall, and were equally impressed with the effects. The woods near Native villages tended to be clear of tangled undergrowth. The widely spaced trees, grass, and pioneering berry bushes created a park-like setting that attracted game, facilitated hunting, and limited the risk of future fires burning out of control. The relative openness of Woodland Period forests also eased long-distance travel. Overland routes developed over thousands of years, crisscrossing tribal territories. Among the most famous was the Old Connecticut Path: it began near present-day Cambridge, following the Quinobequin ("meandering," later Charles) River through Massachusett territory before curving southwest into Nipmuck land. From there, it passed south of present-day Worcester and continued on to the area along the Connecticut River that would eventually become Hartford. (Parts of the route remain heavily traveled today – the Old Connecticut Path is now known as MA Route 9 and MA Route 126.) Europeans arriving in New England did not have to build everything from scratch. They entered a region that already had the equivalent of an international highway system, which they used to expand their settlements. At the dawn of the seventeenth century, modern Native tribes were well-established in Massachusetts. They occupied defined homelands and engineered the environment to facilitate a migratory lifestyle that maximized the yield of local resources. They were also increasingly aware of the world beyond the Atlantic – a world that appeared on the horizon as billowing ship sails, dropped anchor and fishing lines in Massachusetts Bay, and, until 1620, never stayed for long.

Comments are closed.

|

AuthorArchitectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) is working to preserve and redevelop the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as a cutting-edge center for digital innovation. Archives

May 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed