|

The Worcester Memorial Auditorium is often seen as a white elephant, but across the Atlantic, another adaptive reuse project is demonstrating the rewards of rehabilitating a monumental historic treasure. Château de Gudanes is an eighteenth-century palatial mansion nestled in the Pyrenees, and it has seen better days. Built around 1745 on the site of a 13th-century castle, it was the luxurious residence of several generations of French nobles and members of the bourgeoisie. Confiscated during the French Revolution, pillaged four decades later by "Demoiselles" (local residents protesting aristocratic forestry laws), and used as a children's summer camp after WWII, the Château bears witness to 260 years of French history. In the 1990s, plans to redevelop the building as a luxury hotel fell through when the government designated the site as a Class 1 Historic Monument subject to strict restoration regulations. Exposed to the elements and without a caretaker, Château de Gudanes deteriorated. Fortunately, what appeared to be a preservation failure story may be on its way to a fairy-tale ending. The Château spent four years on the real estate market before a young Australian discovered it online in 2011. His parents. Karina and Craig Waters, were intrigued and traveled to France to view the property. Access to the building's interior was forbidden: part of the roof had collapsed, and the consequent water damage and mold had destroyed most of the 93 rooms. Nevertheless, the Waterses immediately fell in love with the crumbling neoclassical palace and its overgrown grounds, framed against steep limestone cliffs. They purchased the property and began renovations in 2013. Since then, the Château has made a slow, but steady recovery. The Waterses have overcome red tape, hired caretakers, and enlisted an army of professionals, locals, and the just plain curious to rehabilitate the building. They intend to accomplish the work as efficiently and sustainably as possible by recycling original features and using locally sourced materials, such as downed wood from the Château parc. Already they have restored floors and walls that had caved in, repainted frescoes, installed hand-made furnishings in stabilized rooms, and seeded the grounds with wildflowers. Nine bedrooms and two kitchens have been rehabilitated and some underfloor heating installed. Locals have shared their knowledge and skills with the restoration team, including a lady who spent a day in the kitchen preparing dishes her grandmother used to make as Château chef. In fact, the Waterses have opened the property during summer to visitors, who are welcome to stay for up to a week as long as they register for a workshop (topics include patisserie baking and fresco restoration) help with the rehabilitation or cooking, and are willing to navigate the building at night by candlelight (all proceeds facilitate the preservation efforts). The couple summed up their vision for the Château on their website: Our aim is to tread lightly and gently - to preserve the atmosphere and authenticity of the Chateau and region as much as possible. She will be renovated but her rawness, wear and history will not be erased, but instead integrated...The Chateau won’t be a pretentious museum piece, but rather, a place to visit, reconnect with the earth and people, and restore the senses, just like she herself has been restored. It won’t be about overcrowding the walls with paintings or overflowing the floors with furnishings, but will be relatively minimalistic - a place to simply rest, breathe and enjoy the calm. Château de Gudanes has a long way to go before it is fully restored, but in the meantime, it remains an inspiration to preservationists like AHF who are pursuing seemingly impossible projects. Though the Aud is worlds away from this palace in the Pyrenees, it shares certain characteristics: a rich history, astounding architecture, and a passionate local community. If the Château de Gudanes - a behemoth tucked away in a remote, mountainous enclave - can be rehabilitated, then surely the Aud - prominently located in a busy district of Worcester - can, too!

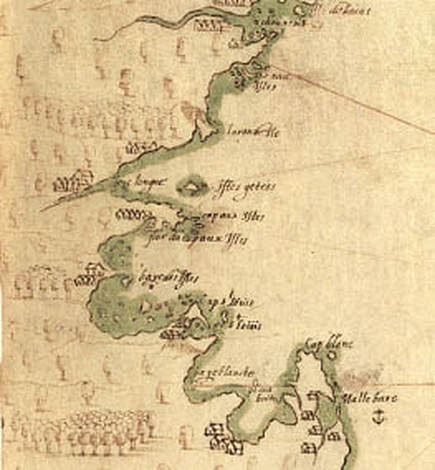

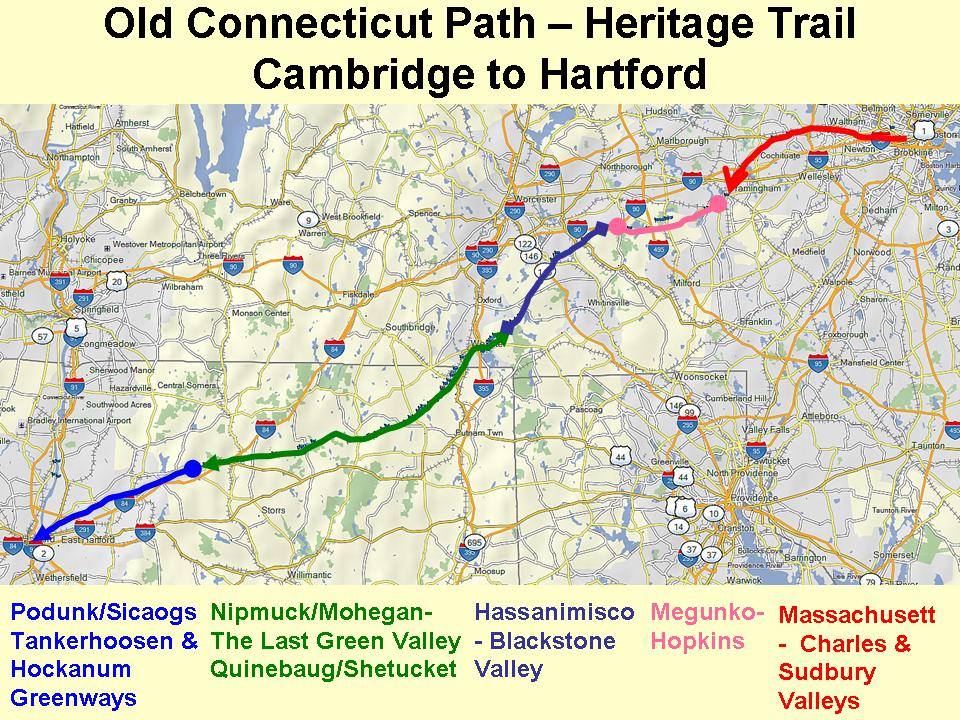

Visit the Château de Gudanes website: https://www.chateaugudanes.com/ When English colonists arrived on the shores of Massachusetts four hundred years ago, they beheld an unfamiliar territory almost devoid of features that might have reminded them of home. There were no carriage paths or cattle pastures, no rooting hogs or crowing roosters, no church steeples or tolling bells. Steep drumlins loomed above the coast, beyond which forests and marshland stretched westward. Mountain lions skulked behind boulders. Wolves howled at night. To settlers accustomed to a treeless countryside subdued beneath the plow, New England was a “vacant wilderness…a place not inhabited but by the barbarous nations.” Little did they understand the way of life that those nations had created over the past three thousand years. Massachusetts during the Woodland Period (3,000-400 BP) was not a pristine wilderness, but an increasingly manipulated landscape home to tens of thousands of Native Americans. As post-glacial sea levels stabilized, Woodland peoples adopted new patterns of habitation and movement that spurred agricultural, technological, and cultural development. Many gravitated toward coastal areas and established long-term seasonal settlements, where they began to plant crops. Initially, they selectively bred weedy vegetation including sunflower, goosefoot, and sumpweed, and boiled the seeds in porridges. By 1000 CE, Central American cultivars – maize, squash, and beans – had arrived in New England and were becoming increasingly important in local diets. Woodland peoples’ migratory lifestyles enabled them to diversify their food sources. Archeological evidence, such as shell middens (ancient trash heaps) on Spectacle Island, suggests that Native Americans settled in large villages during the spring and fall, where they planted and harvested crops, fished, clammed, and hunted, and held political meetings (indeed, in 1614, explorer and colonist John Smith recorded that Native peoples grew maize on the Harbor Islands). During the summer and winter, many villages disbanded. Residents moved to smaller settlements in the region to better exploit food sources while crops ripened or the ground lay frozen. Agriculture transformed the Massachusetts landscape. Though the area remained heavily forested at the time of European contact, patches of cleared ground reflected repeated seasonal use. Native Americans believed that they owned the use of land, rather than the land itself; instead of adopting permanent farming sites, they tilled soil until it was no longer fertile (about eight to ten years) and then relocated. Women cleared new land by setting fires at the base of trees to kill them, and, once the dead wood fell, by burning it away. This method, along with the practice of burning fires all night during both the winter and summer, meant that localized deforestation was common. Thousands of acres near Boston were treeless by 1630; elsewhere, the whitened trunks of girdled trees surveyed cornstalks intertwined with bean and squash vines. Far from a “vacant wilderness,” Massachusetts was an intensively used homeland. Fire enabled local tribes not only to grow crops and stay warm, but also to hunt, gather, and travel. English colonists were astounded that Woodland peoples set large ground fires in the forests during the spring and fall, and were equally impressed with the effects. The woods near Native villages tended to be clear of tangled undergrowth. The widely spaced trees, grass, and pioneering berry bushes created a park-like setting that attracted game, facilitated hunting, and limited the risk of future fires burning out of control. The relative openness of Woodland Period forests also eased long-distance travel. Overland routes developed over thousands of years, crisscrossing tribal territories. Among the most famous was the Old Connecticut Path: it began near present-day Cambridge, following the Quinobequin ("meandering," later Charles) River through Massachusett territory before curving southwest into Nipmuck land. From there, it passed south of present-day Worcester and continued on to the area along the Connecticut River that would eventually become Hartford. (Parts of the route remain heavily traveled today – the Old Connecticut Path is now known as MA Route 9 and MA Route 126.) Europeans arriving in New England did not have to build everything from scratch. They entered a region that already had the equivalent of an international highway system, which they used to expand their settlements. At the dawn of the seventeenth century, modern Native tribes were well-established in Massachusetts. They occupied defined homelands and engineered the environment to facilitate a migratory lifestyle that maximized the yield of local resources. They were also increasingly aware of the world beyond the Atlantic – a world that appeared on the horizon as billowing ship sails, dropped anchor and fishing lines in Massachusetts Bay, and, until 1620, never stayed for long.

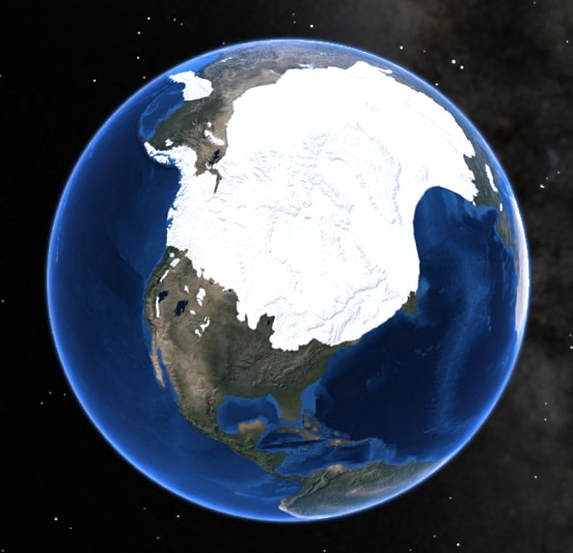

Eighteen thousand years ago, Worcester was smothered beneath 1,800 feet of ice. The blue-white wasteland extended in all directions, burying Mount Wachusett and slowly scouring away the soft sedimentary rock of more recent eons from ancient, underlying schists. Locked in an ice sheet that stretched from the Arctic to present-day New Jersey, Worcester County was unrecognizable: a crevassed expanse of silence reaching toward the rising sun and tumbling into Atlantic waters that were hundreds of feet lower than they are today. The Laurentide ice age was the culmination of one million years of glaciations that dramatically altered the New England landscape. Fluctuating temperatures during the Pleistocene resulted in glaciers repeatedly advancing and retreating across the region. The most recent major ice age – which, according to geologists, is still occurring – began 25,000 years Before Present (BP). Long winters and cool summers caused more snow to fall than melt. The snow eventually compacted under its own weight into an ice sheet that left a rugged legacy in Massachusetts. As the glaciers moved, they accumulated silt, gravel, and even boulders; water seeped into cracks in the bedrock, froze, and expanded, breaking off large chunks of stone that were carried away by the ice. When the ice began to melt around 17,500 BP, it deposited these sediments unevenly throughout the landscape. Leisurely hikes in Worcester County often reveal glacial features: Dexter Drumlin, Purgatory Chasm, eskers in Worcester’s Hadwen Park, erratics in Holbrook Forest, and innumerable wetlands, often the result of poor drainage in areas of tightly packed glacial till. Gradually the ice sheet receded from the region. By 14,000 BP, the barren earth was once again exposed to the sky. Another thousand years would pass before humans braved the tundra of Massachusetts. Archaeological evidence suggests that Paleo-Indians initially settled near major rivers and bodies of water. In 2015, an amateur archaeologist unearthed a small, triangular piece of flint in a Northampton potato field. He recognized it as a what it was right away – a Clovis point arrowhead. Researchers soon confirmed that the arrowhead was 12,800 years old, one of the oldest artifacts ever discovered in the state. Other archaeological sites in Western Massachusetts indicate that Paleo-Indians used the lush Connecticut River Valley as a seasonal hunting ground. Although similar prehistoric evidence is scarcer in Worcester County, fluted points have been found in the Chicopee and Blackstone River Drainages. Local Paleo-Indians likely lived in small, migratory bands, hunting mastodon as well as smaller game and fishing in the region’s many streams and ponds. They adapted to a warming climate that turned the tundra into a vast boreal forest, which, in turn, gave way to hardwoods. By 9,500 BP, ecological change and over-hunting had eradicated the megafauna and created a landscape that would shape humans’ lives for the next nine millennia. Worcester County became more densely populated during the Archaic Period (9,000-3,000 BP). Human settlement spread to present-day West Brookfield, Westborough, and other areas, where archaeologists have discovered projectile points, stone tools, and burial sites. Like their ancestors, Archaic peoples were predominantly hunter-gatherers. They travelled between seasonal hunting grounds in pursuit of game and were deeply familiar with the movements of birds and fish. They mined quartzite from local quarries to fashion weapons and tools, littering the ground with stone flakes that enable today’s archaeologists to identify sites of habitation (such as the Cracked Rock rockshelter in Millbury). Throughout this period, Archaic cultures evolved. The ancient residents of Worcester County adopted new styles of stone and bone craftsmanship as technology improved and fashions changed. They also came to depend more heavily on plant foods, giving rise to the development of local agriculture 3,000 years ago. This milestone was one of many that marked the transition from the Archaic era to the Woodland Period (3,000-450 BP). The millennia preceding European colonization would witness the genesis of contemporary Native American tribes and of the vibrant civilizations that greeted English settlers on the shores of the New World.

|

AuthorArchitectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) is working to preserve and redevelop the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as a cutting-edge center for digital innovation. Archives

May 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed