The Artist's Family: A Conversation with Marie and Jim Rose, Daughter and Grandson of Leon Kroll4/26/2021

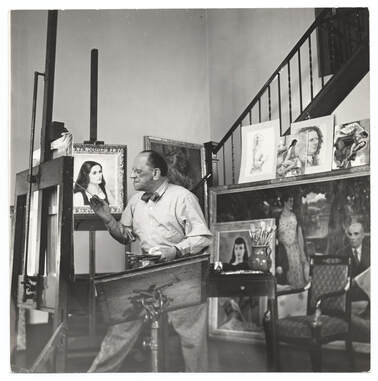

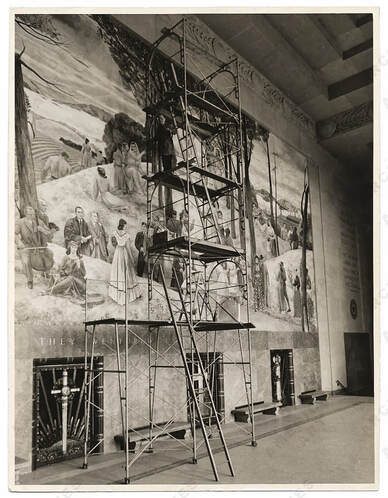

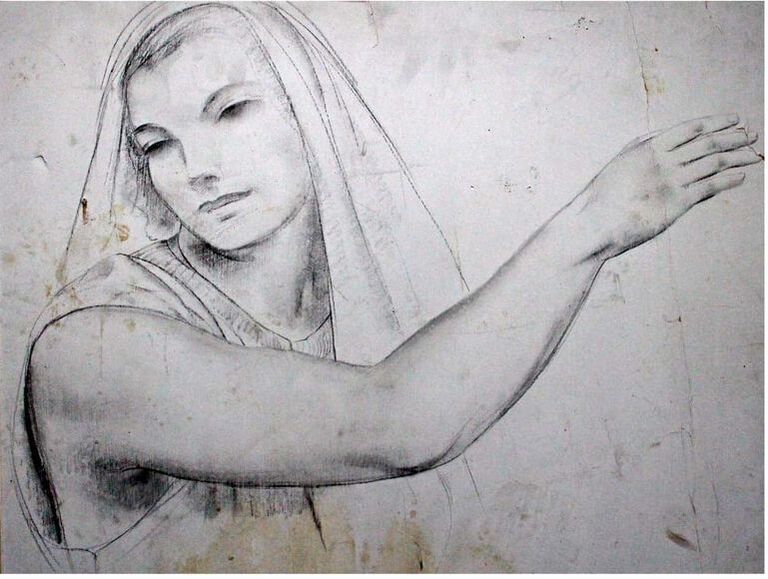

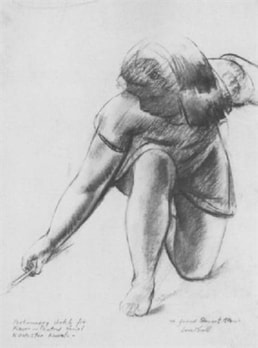

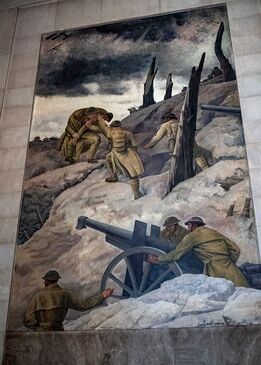

To enter the Shrine of the Immortal at the Worcester Memorial Auditorium is to step into a breathtaking display of devotion. Devotion to the young men and women who sacrificed their lives in a war far from home; devotion to the public and its need to grieve their loss; and above all, devotion to art and its power to heal. The marbled memorial hall echoes with the memories of Worcester’s sons and daughters, whose names are etched in gold on the walls beneath three towering murals painted by renowned artist Leon Kroll. Completed two decades after “the war to end all wars” at the outbreak of a still more terrible conflict, the murals depict in vivid colors scenes of combat and peace, and the everyday heroism of Worcester’s citizenry. In November 2020, AHF staff sat down over Zoom with Kroll’s daughter and grandson, Marie and Jim Rose, to learn more about the artist’s life and work. At 91 years young and with a keen sense of humor, Mrs. Rose is a treasure trove of memories: of a childhood spent in artists colonies during the Great Depression, of her mother Genevieve’s strong influence on her father’s career, of WWII’s impact on her family, and, crucially, of her experience living in Worcester while her father painted the Aud’s murals. Where Mrs. Rose’s recollection faltered, her son Jim affably filled in the gaps and provided some of his own perspectives. The following is an edited and abridged version of the interview.  Leon Kroll. Portrait by Arnold Genthe. Leon Kroll. Portrait by Arnold Genthe. Mrs. Rose, where and when was your father born, and what led him to become an artist? MR: He was born in New York. I knew my grandmother, but my grandfather died before I was on the scene. My grandmother was a lovely lady, she was always doing either knitting, crocheting, or doing embroidery. So that might have influenced my father. Your father was the child of immigrants? JR: Yes, from Poland – MR: Well, now it’s Poland. But then I believe that it was Prussia. Because the name Kroll means “king” in Polish, but they spoke German. What was the path that he took to developing into a young artist? MR: Apparently, he was constantly drawing and seemed to enjoy doing it. Luckily, when he was in high school, he had to take German. Of course, they spoke German at home, so he really didn’t need it, but the German teacher and he did not get along, and he punched the German teacher! They were ready to throw him out of the school. But the principal liked him and said, “Okay, you don’t have to take German anymore, but that will be a free period in which you will have to draw and paint.” So that was great for him! He was happy! JR: He loved drawing, and eventually that drew the attention of C.Y. Turner – he was the president of the Art Students League of New York. Turner was a very well-known murals painter, which undoubtedly inspired my grandfather early in his career. My thought is that [my grandfather] used some good, old-fashioned salesmanship to land an internship with Turner. From meeting Turner, he began his artistic education at age 16 when he enrolled at the course of John Henry Twachtman at the Art Students League of New York. Two years later, at age 18, he entered the National Academy of Design. What influenced your father’s artistic style during those years? MR: It was strongly influenced by the French Impressionists, because he also managed to get himself a scholarship to L’Academie Julian in Paris. I think he spent about two years there [before WWI]. He was absolutely taken by [Paul Cezanne’s] paintings. And he was also strongly influenced by Pierro della Francesca.  "Portrait of Mrs. Kroll in Yellow." Leon Kroll, 1933. From the collections of the Peabody-Essex Museum. "Portrait of Mrs. Kroll in Yellow." Leon Kroll, 1933. From the collections of the Peabody-Essex Museum. Eventually, he returned to the United States and worked as an artist, but then he made it back to France, where he met your mother, [Genevieve Domec]? MR: That was in 1923. He was in a marrying mood, and most of the girls he went around with thought he was too old. They suggested that he go to France, because French women tended to marry older men, probably because they were more secure, I don’t know. He [had] a friend, an artist called Robert Delaunay, [who] was a Cubist, and his wife Sonia Delaunay, [who] designed the sets for the Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo. Dad said, “Do you know a nice French girl?” And they said “Yes, but she’s very proper.” So Sonia called up my mother, she showed up... Then mother told him, “I’m going to Malmaisson-en-Seine” – where my grandparents had a summer place – “and anybody who wants to come, come.” The only person who showed up was my father! Apparently, he impressed my uncle Pierre by being a very powerful swimmer, because my grandparents’ property was just about a field away from the River Seine, and he knew how to swim against the current. Within six weeks of knowing [my mother,] he proposed. And she married him! And eventually your father persuaded your mother to immigrate to the United States? MR: Yes. First they lived in Chicago, because Dad got a job at the art institute. And Mother said about Chicago, she just couldn’t take the cold winters, but she met the loveliest bunch of people there. There was a story, too, about the window washer – he was sort of a tip-off man for [mobster Charles] O’Banion in Chicago – who said, “You shouldn’t steal anything [from the Krolls’ home], there’s nothing but paintings!” My mother said, “We felt terribly snubbed!” How did your mother support her husband’s work? MR: She was a fabulous cook. They did a lot of adult entertaining. JR: She had good salesmanship – sales and marketing skills. MR: Oh, yes – they were constantly entertaining. So that certainly helped my father’s business.  Leon Kroll in His Studio, 1931. Photo by Jane Rogers. From collections of the Archives of American Art. Leon Kroll in His Studio, 1931. Photo by Jane Rogers. From collections of the Archives of American Art. What was your father and your grandfather like in person? MR: As an artist, I would describe him as very disciplined. In the morning, he would go out and do scenery, but in the afternoon, he always had a model that he drew. Every day he drew. He took his work seriously. And as a person, I would say – he was liberal in his politics, but never a Communist. He had one experience with a Soviet-American friendship, and he left it very quickly after, he realized they were a Communist front organization, and he wanted nothing to do with them. He was more into what was going on with the National Academy of Design, the American Institute of Arts and Letters, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was more into that than he was into politics or anything like that. Also I would say that as far as his Jewishness was concerned, he was not a practicing Jew. However, the one interesting thing about my father was, we were required to wash our hands before we had a meal. And also, yes, he liked his scotch-on-the-rocks before dinner, but he didn’t drink very much, and he liked good food, but he wasn’t a particularly picky eater. Of course, my mother was a superb cook. Unfortunately, she just didn’t have the patience to teach me anything. If I was doing something wrong, she would grab it from me. I guess she just didn’t want to see her beautiful work ruined.  "Appletrees, Woodstock." Leon Kroll, 1922. From Sotheby's website. "Appletrees, Woodstock." Leon Kroll, 1922. From Sotheby's website. You were born just in time for the Great Depression to hit. What do you remember from that period, and how did your father manage to keep making art? MR: I think they did have problems during the Depression, like most people did. Mother was wondering how she could support me, and she wrote to my grandmother about that, but – [shudders] I didn’t particularly like a summer I spent in France when I was six with my grandmother. My grandmother felt that I was badly behaved, so she decided that she had to apply la discipline! She was very, very strict. I can remember if I didn’t like some food, oh God, there was no end of scolding. I mean, she was just scold, scold, scold. JR: My mother never lived outside the States. [But] she moved around a lot. MR: Oh, yes. We lived in New York in the winter until I was nine. Then my father, fortunately, got to paint the murals in the Attorney General’s office. And then he entered the competition for the paintings in the Worcester Memorial Auditorium… Dad had to do the sketches for the Worcester murals, so we rented his sister Jane’s house in Bearsville, NY. I spent a rather nice year there, where I went to a one-room schoolhouse! We skated, and we skied, and there was a lot of winter sport, and also a lot of nature study – the teacher was very strong on that. And for a one-room schoolhouse, I actually learned a fair amount. Before that I’d gone to the Lennox School in New York, and I always felt I was the poor relation there. What it was like to learn in a one-room schoolhouse? MR: It was a combination of the natives, and then the artists who would want to hang around Woodstock and Bearsville and would dump their kids in the one-room schoolhouse from September to November. Then they would go back to New York…and then, come spring, [the parents] decided, “Oh, we want to go back to Bearsville, the Catskills,” and then some of the kids would be dumped into the one-room schoolhouse with all the natives. I can remember we had certain textbooks that we read and talked about, and also we had to read to the younger children. So the school, although it certainly didn’t have the philosophy of progressive education, I guess you could say in practice it was progressive education. Do you remember the details of the competition to paint the Worcester Memorial Auditorium murals, and who else entered? JR: We do know who some of the judges were. The Worcester World War Memorial Commission included Ralph Earle, George Barton, Edward Hayes, Charles Allen, George Booth – he was the Chairman – Michael O’Hara, George Fuller, John White, and Harrison Taylor. They were all businesspeople or lawyers, highly regarded citizens of Worcester. What years did you live in Worcester? MR: We came there in the fall of 1939, and we left in the spring of 1941. I can remember Dad having the radio on and hearing about Hitler’s invasion of Poland. Mother wanted to go back to France to visit her family. My father said, “No. Too dangerous. But I will sponsor one of your family to come to the United States.” So Mother’s younger brother, Claude – he was an artist, and he designed tapestries for Aubusson – he came over. He lived with us when we were in Bearsville and also when we were in Worcester. Uncle Claude was a nice guy, but what I remember about him, and that really got me angry with him, [was that] he never felt the need to learn English… I think he understood more than he spoke. Because he did have a job at the Metropolitan Museum and did all the swear words, but not much else. But he didn’t like it when he heard it from me!  Leon Kroll painting a mural in the Worcester Memorial Auditorium, 1935. Source: https://elhurgador.blogspot.com/2013/10/manos-la-obra-xxvi.html. Leon Kroll painting a mural in the Worcester Memorial Auditorium, 1935. Source: https://elhurgador.blogspot.com/2013/10/manos-la-obra-xxvi.html. Do you remember any discussion between your father and your mother regarding the decision to move to Worcester? JR: My grandmother was not particularly excited about going to Worcester. MR: No, she wasn’t. And she was very unhappy there. I think that [my parents] managed to get into the wrong crowd of people. They were just a whole bunch of very snooty WASPS that looked down on her. Mother said that when France got defeated, the snobs in Worcester wouldn’t speak to her. And I guess [my parents] just didn’t realize the fact that Worcester was a [city] that had colleges…and also that there were professional people in Worcester that might have been more accepting of her than these so-called snooty WASPS. But she did make good friends with the writer Esther Forbes, and also this crazy lady, Mrs. Snow. Mother [told] a story about Mrs. Snow, that she had the artist Paul Sample over to lunch…and she was looking at Paul Sample and saying, “Oh, those big blue eyes!” So she was always propositioning people! I can remember going to Christmas parties at Mrs. Snow’s, she’d have a nice punch and what have you, and it was a lovely party. And when I went to Bancroft, she talked to us about her trips in Europe. But Mother liked her, because the way she handled Worcester was, she just did her own thing and couldn’t have cared less what the other people thought. How did you handle Worcester? MR: Well – I did and I didn’t. The first year I spent at the Bancroft School, which was a private school, and while I learned a lot there, the children were just so mean to me! They criticized my clothes constantly, because I remember having bought clothes that were appropriate for Bearsville, NY, but not for Worcester [or] for the Bancroft School. So I was constantly being ridiculed about my clothes, and I felt that was pretty nasty. I just didn’t want to go to that school again, so I ended up at Sever Prep. Now, Sever Prep, the kids were great, everybody was nice. But I don’t think I learned as much as I did at the Bancroft School. What was the process of creating and then executing the murals? MR: He did the sketches in Bearsville, and then when he was working on the mural, he enlarged it. However, during the course of that, he fell off the scaffold and broke his leg! He went to Memorial Hospital in Worcester, and he happened to have an excellent surgeon called Dr. Johnson. He was just out of commission for about six weeks. He did some drawings and stuff in the house where we were living, and he had somebody helping him out who was also one of his models, Gloria Rathay. She was the blonde gal with the braids [in the Aud’s center mural]. And she also did secretarial work for him, so he was productive while he was laid up at the house. Was your father the only person who painted the murals? MR: No, he had two assistants, Claude and an artist called Nick Corone, helping him out. Claude did the leaves, and then Nick would do something else. Things like the trees and the leaves, the assistants did. I think [my father] did more of the people. Do you recognize any of the people depicted in the murals? MR: This lady in the foreground [of the center mural] with the black hat and the black print dress seems to look like my mother. Also, the person who is putting the wreath on the coffin of the soldier looks like Gloria Rathay, because I remember she was a blonde with braids. I can’t tell you what some of the other people were. For the sketches, some were from Bearsville, but then when he went to Worcester, he also needed live models, so he used some people from Worcester for that. How often did your mother pose for your father? MR: On-ishly and off-ishly. She didn’t like posing, because you had to sit still and not say anything. I’ve posed for him. And it isn’t the greatest of things to have to do. You had to have infinite patience and be willing to keep your mouth shut, because Daddy was concentrating. What do you remember of Gloria Rathay? MR: She lived on South Flagg Street in Worcester, and her father was a contractor, and he had built all the houses on Flagg Street. I don’t know how Dad came in contact with her, but I guess he saw her somewhere and that she had the right hair or something like that. And that while she was posing for him, she also did secretarial work for him. Do you remember any men posing for him as World War I soldiers in the Army and Navy murals? MR: No, not really. I don’t know whether the guy with the sweatshirt was Nick Corone, one of his assistants. I do know more about the naval story… My father had painted the floor of the battleship grey. And somebody told him, “No. The floor of the battleships were painted yellow.” So he had to change the color. Do you know what happened to any of the models for these murals after World War II broke out? MR: I really don’t know. Because we moved away and lost touch. Did you or your father ever visit the Auditorium after he completed the murals? MR: Once, several years after. I thought [the murals] were lovely! And certainly well-crafted and certainly well-worth saving. JR: We’re hoping you guys can put together some financing, even in this COVID situation, and hopefully restore that building to the way it was seventy years ago. Jim, have you visited the Aud? JR: Yes, Preservation Worcester hosted a fundraiser at the Auditorium back in 2013, and Julie and I went to that. So that was pretty exciting. Why is the Aud important to you? JR: It was a game-breaker for my grandfather, it really helped put him on the map. MR: Of course, he had been put on the map with the Attorney General’s office murals before that, but he got the Indiana commission and also the Johns Hopkins commission certainly as a result of [the Worcester murals]. What do you hope will happen with the Worcester Memorial Auditorium? JR: Well, we want you to close the financing, we want you to get this deal done. MR: Yes, because I think it’s certainly a beautiful mural, and it should be preserved. The Worcester Memorial Auditorium is a redevelopment project by the Architectural Heritage Foundation (AHF), a 501(c)3 dedicated to stimulating economic development in under-resourced communities through historic preservation. Follow the Aud project on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

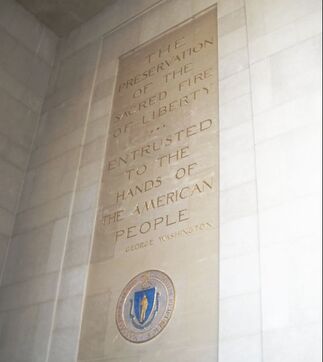

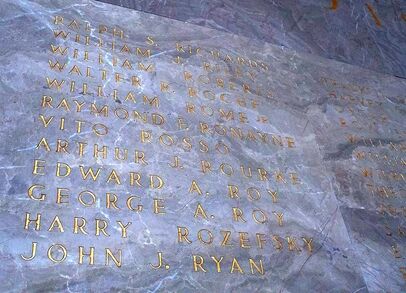

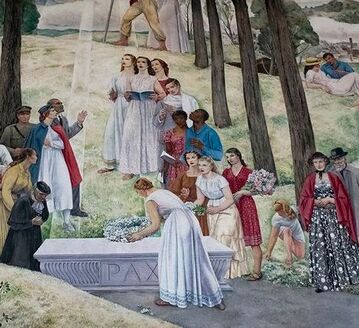

“The preservation of the sacred fire of liberty…entrusted to the hands of the people." - George Washington “The preservation of the sacred fire of liberty…entrusted to the hands of the people." - George Washington Oscar Larsson was twenty-one when he modelled for Leon Kroll. Blonde and barrel-chested, the former high school football star posed shirtless, grasping a long pole as the artist sketched. Within a few months, Kroll had immortalized Oscar in a sprawling mural at the Worcester Memorial Auditorium. The young Worcester native is depicted receiving an American flag from a WWI soldier ascending to heaven. “The irony of all this is, [the mural] was finished in May 1941, and in December 1941 we went to war,” 98-year-old Oscar told the Worcester Telegram and Gazette in 2018. “So the flag was passed to the next generation, and I was part of it. I went into the service myself after that.” Service, sacrifice, and hope for a better world – these are the cornerstones of a building conceived and constructed during crisis. Nowhere in the Aud are these values more apparent than in the Shrine of the Immortal, the memorial hall where Oscar stands frozen in time above the names of Worcester’s WWI fallen, surrounded by painted figures whose lives also would soon be upended – and perhaps ended – by the Second World War. Created at the height of the Great Depression, in the interlude between two global conflicts, and in the wake of the Spanish influenza, the Shrine of the Immortal is at once a testament to past challenges and an aspiration for a more harmonious future. The stories it contains speak to our own tumultuous era.  The names of Worcester's fallen WWI soldiers and nurses inscribed in the Shrine of the Immortal. Photo courtesy of MassLive. The names of Worcester's fallen WWI soldiers and nurses inscribed in the Shrine of the Immortal. Photo courtesy of MassLive. The fact that the Aud was built at all is remarkable considering the dire state of Worcester’s economy in 1931-1933. The industrial city was among the hardest hit in Massachusetts by the stock market crash. Factories halted production and unemployed mill workers formed breadlines that snaked through the streets. Yet Worcester leaders pressed ahead with the Aud’s construction. They put people to work on a $2 million civic infrastructure project that anticipated the Works Progress Administration endeavors. In 1933, the completed building was dedicated before a crowd of spectators as “an enduring tribute to those whose sacrifice was sublime, a majestic memorial for the use and benefit of many generations." And use it people did. During the week following the dedication, Worcester residents enjoyed concerts and other events in the auditorium that provided brief, but much-needed respite from the anxieties of the Depression. At a time of acute financial hardship, the City leadership provided jobs to many and a space for cultural expression to all. The Aud was also intended as a space for healing in the wake of a global conflict and pandemic. Inscribed on the Shrine of the Immortal’s marble walls are the names of 355 young men and women whose lives were cut short during WWI. Many were buried far from home or lost at sea. In lieu of a grave, their bereft loved ones came to the Aud, searched for their names, and sat in reflection upon the stone benches beneath Leon Kroll’s towering murals. Morris Bailey’s family would have remembered a teenage boy who left high school and a comfortable homelife to enlist with an aero squadron; who survived two years of war, making a surprise visit home for Christmas in 1918; who was recalled into service the following year in anticipation of post-armistice violence and died in a training plane crash at age nineteen. Aurelia and Horace Wyman’s sister, Louisa, would have recalled her two siblings – a war nurse and a lieutenant, respectively – who both died of influenza in Europe, where she, herself, was also serving as a nurse. And as a new generation of youth marched off to the battlefields of WWII, those they left behind might have found solace beneath the words of George Washington, carved beside Leon Kroll’s newly completed mural: “The preservation of the sacred fire of liberty…entrusted to the hands of the people."  Detail from Leon Kroll's mural in the Shrine of the Immortal. Original photograph courtesy of MassLive. Detail from Leon Kroll's mural in the Shrine of the Immortal. Original photograph courtesy of MassLive. Though rooted in remembrance, the Shrine of the Immortal also aspired to a more peaceful and equitable future. At a time when Jim Crow and redlining widened racial divisions, the Great Depression ravaged the lives of low-income people, and New Deal-era muralists painted sanitized images of oppression, Leon Kroll depicted a world in which "people of all classes and races gathered in peace and harmony under the American flag." The people shown are laborers, soldiers, nurses, musicians, mothers. They are Black and white, young and old. Side by side, they devote their energy to building a more prosperous Worcester and their prayers to building a more peaceful world. Behind its imposing granite columns, the Aud offers guidance for our own troubled generation. It is a tangible lesson on the importance of a communal response to crisis. The building exists thanks to those who labored through financial hardship to create a public gathering space for the benefit of people they did not know. Its stones bear the stories of those who willingly risked their lives in battle and on hospital wards. Its murals envision a more just society. Ultimately, the Aud reminds us that there is work to be done in service of something larger than ourselves, and that the surest way to accomplish it – especially during turbulent times – is by coming together. |

AuthorArchitectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) is working to preserve and redevelop the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as a cutting-edge center for digital innovation. Archives

May 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed