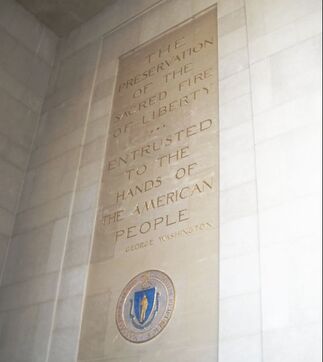

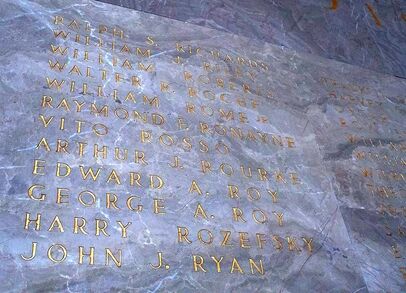

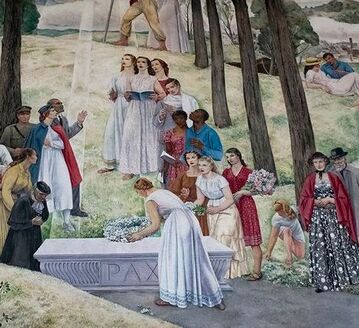

“The preservation of the sacred fire of liberty…entrusted to the hands of the people." - George Washington “The preservation of the sacred fire of liberty…entrusted to the hands of the people." - George Washington Oscar Larsson was twenty-one when he modelled for Leon Kroll. Blonde and barrel-chested, the former high school football star posed shirtless, grasping a long pole as the artist sketched. Within a few months, Kroll had immortalized Oscar in a sprawling mural at the Worcester Memorial Auditorium. The young Worcester native is depicted receiving an American flag from a WWI soldier ascending to heaven. “The irony of all this is, [the mural] was finished in May 1941, and in December 1941 we went to war,” 98-year-old Oscar told the Worcester Telegram and Gazette in 2018. “So the flag was passed to the next generation, and I was part of it. I went into the service myself after that.” Service, sacrifice, and hope for a better world – these are the cornerstones of a building conceived and constructed during crisis. Nowhere in the Aud are these values more apparent than in the Shrine of the Immortal, the memorial hall where Oscar stands frozen in time above the names of Worcester’s WWI fallen, surrounded by painted figures whose lives also would soon be upended – and perhaps ended – by the Second World War. Created at the height of the Great Depression, in the interlude between two global conflicts, and in the wake of the Spanish influenza, the Shrine of the Immortal is at once a testament to past challenges and an aspiration for a more harmonious future. The stories it contains speak to our own tumultuous era.  The names of Worcester's fallen WWI soldiers and nurses inscribed in the Shrine of the Immortal. Photo courtesy of MassLive. The names of Worcester's fallen WWI soldiers and nurses inscribed in the Shrine of the Immortal. Photo courtesy of MassLive. The fact that the Aud was built at all is remarkable considering the dire state of Worcester’s economy in 1931-1933. The industrial city was among the hardest hit in Massachusetts by the stock market crash. Factories halted production and unemployed mill workers formed breadlines that snaked through the streets. Yet Worcester leaders pressed ahead with the Aud’s construction. They put people to work on a $2 million civic infrastructure project that anticipated the Works Progress Administration endeavors. In 1933, the completed building was dedicated before a crowd of spectators as “an enduring tribute to those whose sacrifice was sublime, a majestic memorial for the use and benefit of many generations." And use it people did. During the week following the dedication, Worcester residents enjoyed concerts and other events in the auditorium that provided brief, but much-needed respite from the anxieties of the Depression. At a time of acute financial hardship, the City leadership provided jobs to many and a space for cultural expression to all. The Aud was also intended as a space for healing in the wake of a global conflict and pandemic. Inscribed on the Shrine of the Immortal’s marble walls are the names of 355 young men and women whose lives were cut short during WWI. Many were buried far from home or lost at sea. In lieu of a grave, their bereft loved ones came to the Aud, searched for their names, and sat in reflection upon the stone benches beneath Leon Kroll’s towering murals. Morris Bailey’s family would have remembered a teenage boy who left high school and a comfortable homelife to enlist with an aero squadron; who survived two years of war, making a surprise visit home for Christmas in 1918; who was recalled into service the following year in anticipation of post-armistice violence and died in a training plane crash at age nineteen. Aurelia and Horace Wyman’s sister, Louisa, would have recalled her two siblings – a war nurse and a lieutenant, respectively – who both died of influenza in Europe, where she, herself, was also serving as a nurse. And as a new generation of youth marched off to the battlefields of WWII, those they left behind might have found solace beneath the words of George Washington, carved beside Leon Kroll’s newly completed mural: “The preservation of the sacred fire of liberty…entrusted to the hands of the people."  Detail from Leon Kroll's mural in the Shrine of the Immortal. Original photograph courtesy of MassLive. Detail from Leon Kroll's mural in the Shrine of the Immortal. Original photograph courtesy of MassLive. Though rooted in remembrance, the Shrine of the Immortal also aspired to a more peaceful and equitable future. At a time when Jim Crow and redlining widened racial divisions, the Great Depression ravaged the lives of low-income people, and New Deal-era muralists painted sanitized images of oppression, Leon Kroll depicted a world in which "people of all classes and races gathered in peace and harmony under the American flag." The people shown are laborers, soldiers, nurses, musicians, mothers. They are Black and white, young and old. Side by side, they devote their energy to building a more prosperous Worcester and their prayers to building a more peaceful world. Behind its imposing granite columns, the Aud offers guidance for our own troubled generation. It is a tangible lesson on the importance of a communal response to crisis. The building exists thanks to those who labored through financial hardship to create a public gathering space for the benefit of people they did not know. Its stones bear the stories of those who willingly risked their lives in battle and on hospital wards. Its murals envision a more just society. Ultimately, the Aud reminds us that there is work to be done in service of something larger than ourselves, and that the surest way to accomplish it – especially during turbulent times – is by coming together. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorArchitectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) is working to preserve and redevelop the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as a cutting-edge center for digital innovation. Archives

May 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed