|

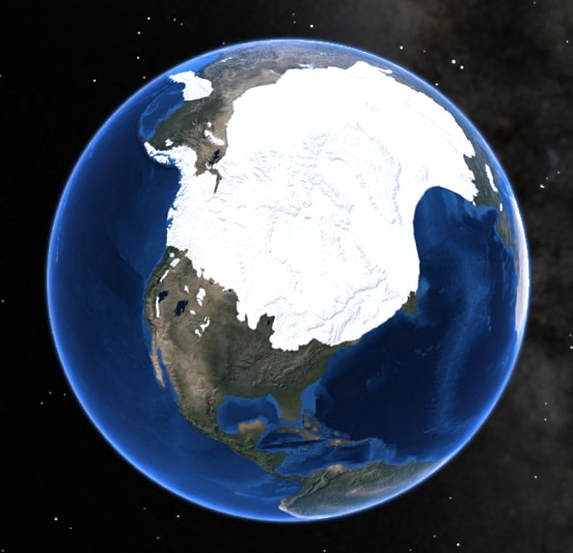

Eighteen thousand years ago, Worcester was smothered beneath 1,800 feet of ice. The blue-white wasteland extended in all directions, burying Mount Wachusett and slowly scouring away the soft sedimentary rock of more recent eons from ancient, underlying schists. Locked in an ice sheet that stretched from the Arctic to present-day New Jersey, Worcester County was unrecognizable: a crevassed expanse of silence reaching toward the rising sun and tumbling into Atlantic waters that were hundreds of feet lower than they are today. The Laurentide ice age was the culmination of one million years of glaciations that dramatically altered the New England landscape. Fluctuating temperatures during the Pleistocene resulted in glaciers repeatedly advancing and retreating across the region. The most recent major ice age – which, according to geologists, is still occurring – began 25,000 years Before Present (BP). Long winters and cool summers caused more snow to fall than melt. The snow eventually compacted under its own weight into an ice sheet that left a rugged legacy in Massachusetts. As the glaciers moved, they accumulated silt, gravel, and even boulders; water seeped into cracks in the bedrock, froze, and expanded, breaking off large chunks of stone that were carried away by the ice. When the ice began to melt around 17,500 BP, it deposited these sediments unevenly throughout the landscape. Leisurely hikes in Worcester County often reveal glacial features: Dexter Drumlin, Purgatory Chasm, eskers in Worcester’s Hadwen Park, erratics in Holbrook Forest, and innumerable wetlands, often the result of poor drainage in areas of tightly packed glacial till. Gradually the ice sheet receded from the region. By 14,000 BP, the barren earth was once again exposed to the sky. Another thousand years would pass before humans braved the tundra of Massachusetts. Archaeological evidence suggests that Paleo-Indians initially settled near major rivers and bodies of water. In 2015, an amateur archaeologist unearthed a small, triangular piece of flint in a Northampton potato field. He recognized it as a what it was right away – a Clovis point arrowhead. Researchers soon confirmed that the arrowhead was 12,800 years old, one of the oldest artifacts ever discovered in the state. Other archaeological sites in Western Massachusetts indicate that Paleo-Indians used the lush Connecticut River Valley as a seasonal hunting ground. Although similar prehistoric evidence is scarcer in Worcester County, fluted points have been found in the Chicopee and Blackstone River Drainages. Local Paleo-Indians likely lived in small, migratory bands, hunting mastodon as well as smaller game and fishing in the region’s many streams and ponds. They adapted to a warming climate that turned the tundra into a vast boreal forest, which, in turn, gave way to hardwoods. By 9,500 BP, ecological change and over-hunting had eradicated the megafauna and created a landscape that would shape humans’ lives for the next nine millennia. Worcester County became more densely populated during the Archaic Period (9,000-3,000 BP). Human settlement spread to present-day West Brookfield, Westborough, and other areas, where archaeologists have discovered projectile points, stone tools, and burial sites. Like their ancestors, Archaic peoples were predominantly hunter-gatherers. They travelled between seasonal hunting grounds in pursuit of game and were deeply familiar with the movements of birds and fish. They mined quartzite from local quarries to fashion weapons and tools, littering the ground with stone flakes that enable today’s archaeologists to identify sites of habitation (such as the Cracked Rock rockshelter in Millbury). Throughout this period, Archaic cultures evolved. The ancient residents of Worcester County adopted new styles of stone and bone craftsmanship as technology improved and fashions changed. They also came to depend more heavily on plant foods, giving rise to the development of local agriculture 3,000 years ago. This milestone was one of many that marked the transition from the Archaic era to the Woodland Period (3,000-450 BP). The millennia preceding European colonization would witness the genesis of contemporary Native American tribes and of the vibrant civilizations that greeted English settlers on the shores of the New World.

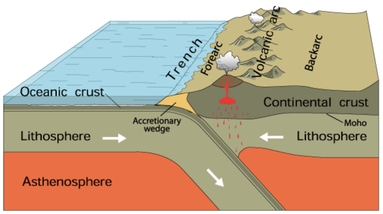

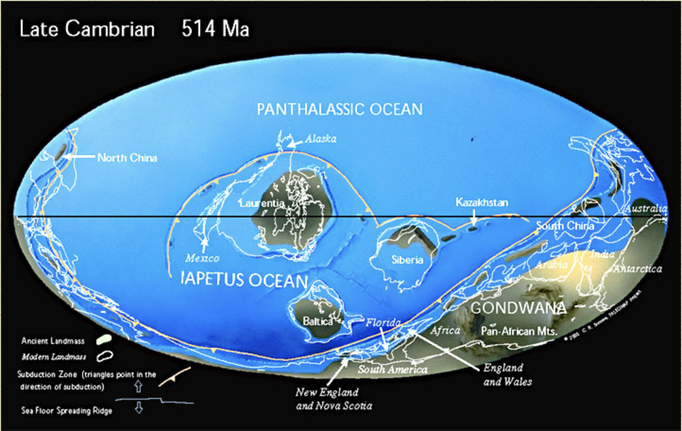

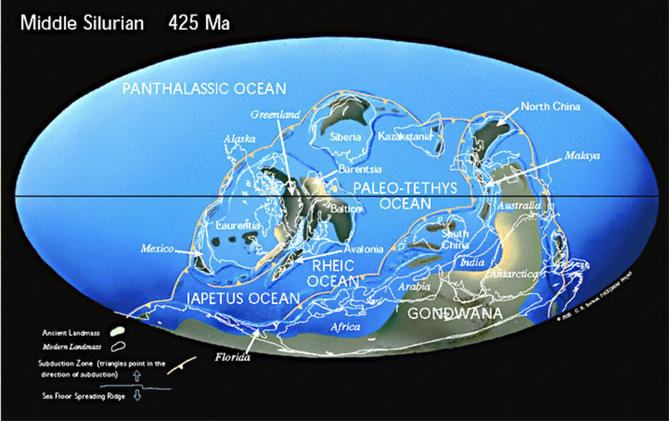

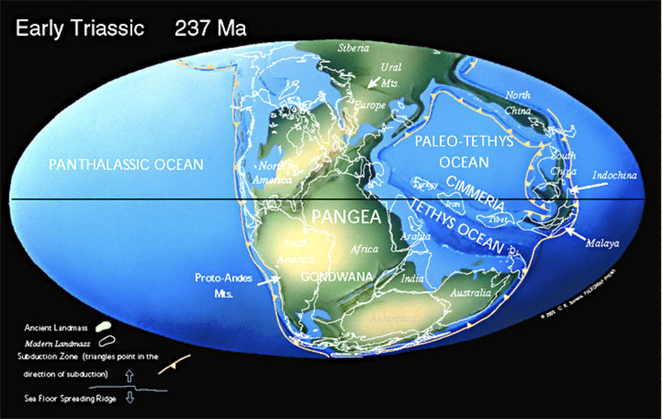

Subduction. Courtesy of USGS. Subduction. Courtesy of USGS. Imagine a world where South America is at the South Pole, Siberia, along the Tropic of Capricorn, and Greenland, at the Equator. In this world, Florida is a frigid strip of coast connecting South America and Africa. Canada bakes beneath a bright equatorial sun. The rest of North America is a scuba-diver's paradise – assuming scuba-divers numbered among the primitive, single-cell organisms that existed 550 million years ago. Welcome to the Late Precambrian, an era of dramatic geological change and the beginning of New England’s story. At this point, the earth was 3.5 billion years old. It had already experienced multiple episodes of continental drift, volcanism, and glaciation. The Grenville Mountain chain, formed during an earlier period of tectonic collision, had eroded. All that remained was a small layer of bedrock and a large amount of sediment that would eventually become western Massachusetts. Three major continents contained most of the planet’s land mass: Laurentia, Baltica, and the supercontinent Gondwana, whose coastline roiled with volcanic activity. The earthquakes and lava flows were symptoms of tectonic subduction (when one tectonic plate dives beneath another) and rifting (when two plates diverge). Over time, these subterranean stirrings formed the Avalon mountain range and Boston Rift Basin off the coast of present-day South America. We now call this region New England. As Earth entered the Cambrian Period, Avalon broke away from Gondwana. Sediments filled the rift basin and compressed into the Cambridge Argillite and Roxbury Conglomerate (puddingstone) rock formations underlying Greater Boston today. Between 430 and 390 million years ago, Avalon collided with Laurentia, forming the Northern Appalachians. This period of tectonic uplift coincided with rising oxygen levels and an explosion of multicellular life. Complex organisms spread across the globe as New England rose from the depths of the ocean. Over the succeeding eons, the planet’s crust continued to transform. The continents collided again 250 million years ago to form Pangaea, lifting the Appalachians to Himalayan heights, and then separated fifty million years later. This period of rifting created today’s continents and instigated more lava flows. We can still see evidence of this geological turbulence in the igneous and metamorphic rocks of Worcester County. Volcanic activity subsided as the continents drifted to their present locations. Massachusetts was thereafter shaped by deposition, weathering, and erosion. Temperatures rose, fell, and rose again, causing frequent glaciations that carved the Northeastern bedrock. Meanwhile, life evolved. The region was alternately submerged in shallow seas teeming with crustaceans and fish, and raised high and dry, a coastal forest where dinosaurs roamed. By the time Homo sapiens arrived in New England twelve thousand years ago, the region was a frozen tundra. The latest Ice Age scarred the landscape with eskers, dimpled it with kettle ponds, and pimpled it with erratics – a rugged topography that determined where humans settled, and upon which they would eventually unleash their transformative might.

|

AuthorArchitectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) is working to preserve and redevelop the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as a cutting-edge center for digital innovation. Archives

May 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed