|

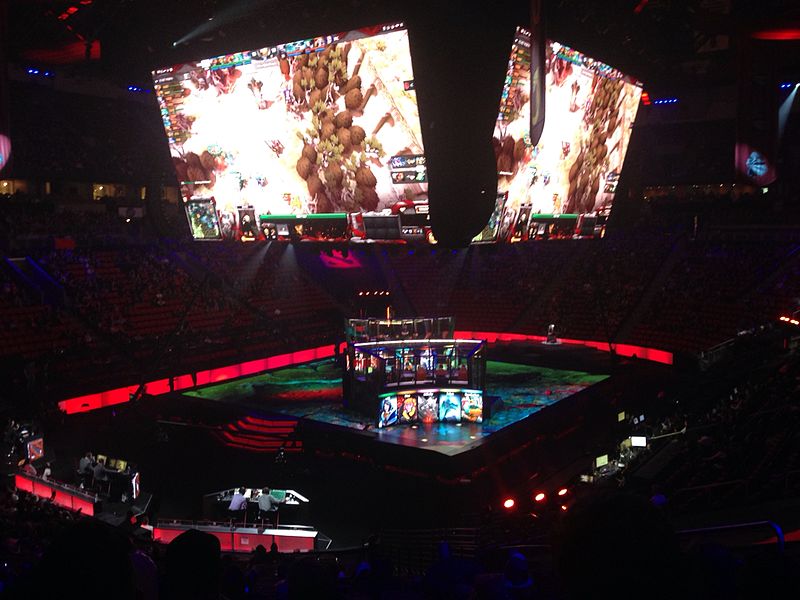

As the novel coronavirus shuts down stadiums and theaters across the country, one entertainment industry sees opportunity in the cancelled events. Esports, which in 2019 commanded a global audience of more than 433 million, is poised to grow as people seek socially distant forms of entertainment.

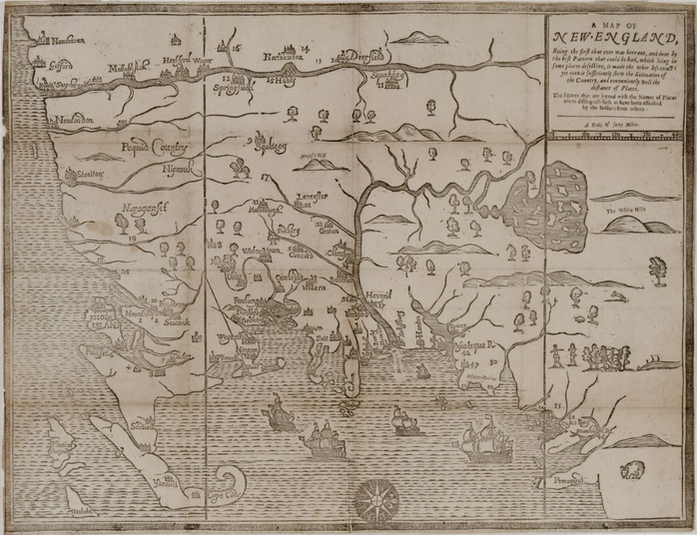

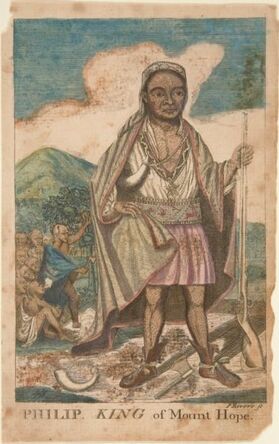

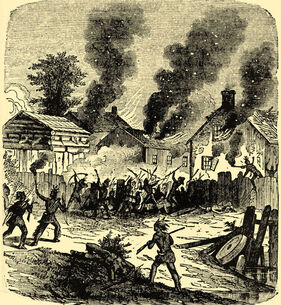

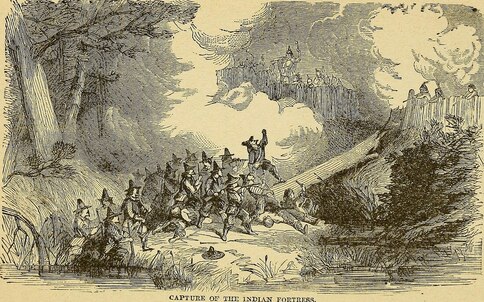

The industry's advantage lies in its flexibility. Unlike athletic games and artistic performances, esports competitions can be held entirely online, with gamers facing each other remotely in matches live-streamed to far-flung audiences numbering in the millions. The closure of schools, offices, and traditional entertainment venues in China has already led to a significant spike in esports viewership. According to the Washington Post, the esports organization Gen.G reported an increase of 18.2 percent in Chinese viewership on two of its live-streaming sites for its Player Unknown's Battlegrounds and League of Legends teams. Meanwhile, over the past week the streaming app Twitch saw increases in first-time downloads of 50 percent, 41 percent, and 26 percent in Greece, Italy, and Spain, respectively, and 14 percent in the United States, which is still in the early stages of quarantine. "There is an opportunity to expand their audiences," according to video gaming market analyst Michael Pachter, quoted in the Post. "It won't expand by 50 percent, but it could possibly expand by 20 percent." The coronavirus has, of course, presented challenges to the esports industry. In recent years, esports leagues have held live tournaments in both designated and makeshift venues, which can attract audiences in the tens of thousands. The social aspect of these often multi-day events is often as important as the competition itself. Spectators alternate between watching the professional games, playing each other, and patronizing esports vendors. Numerous tournaments have been cancelled as venues shut down over public health concerns. Nevertheless, the opportunities for virtual gaming and live-streaming promise to introduce new viewers to esports, expanding the industry's reach. A rise in the popularity of esports presents opportunities not only to gaming professionals, but to adjacent industries. Development projects like the Aud will be well-positioned to take advantage of the growth of esports once the economy - and daily life - returns to normal.  "A Map of New England," originally published in William Hubbard's "Narrative of the Troubles with the Indians," 1677. Massachusetts Historical Society. Oriented with the West at top, the map uses numbers to represent communities attacked by Native fighters - the number 17 (slightly left of center) denotes Quinsigamond Plantation. The city of Worcester got off to a rocky start. Quinsigamond Plantation, as it was called in 1675, was located in New England’s western frontier. Like other nearby colonial outposts, it had sprung up along the Boston Post Road to satisfy land-hungry colonists and expand Massachusetts territory, often at the expense of indigenous populations. The village had been purchased for a pittance from the local Nipmuc in 1674. Lots ranging in size from 25 to 100 acres had been laid out on “Indian broken up lands,” the settlers’ term for former Native agricultural areas. A two-story, wooden garrison house – the “old Indian Fort” – guarded the plantation and the approximately thirty Englishmen who called it home. Relations between the Quinsigamond Plantation settlers and the Nipmuc were initially calm, though colonial authorities tried to exert political influence over their Native neighbors. In September 1674, the Reverend John Eliot and Daniel Gookin visited the nearby village Pakachoag, where they were “kindly entertained” by sagamores Horowanninit (known to the English as Sagamore John) and Woosanakochu. Eliot and a Christianized Nipmuc minister, James Speen, preached and led a prayer service. A resident council then approved the two sagamores “to be rulers of this people and co-ordinate in power, clothed with the authority of the English government” and accepted Speen as their minister. It is unclear whether the villagers did so because they sought the colonial government’s protection or simply to humor their visitors. Whatever the case, the outbreak of King Philip’s War disrupted all efforts to forge tighter bonds between European authorities, Quinsigamond Plantation, and the Nipmuc.  Paul Revere's imaginative depiction of Metacomet, 1772. Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery. Paul Revere's imaginative depiction of Metacomet, 1772. Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery. Largely forgotten in public memory today, King Philip’s War was the bloodiest conflict in American history. What began as a Native rebellion against English colonization morphed into a war of extermination whereby the Wampanoag, Massachusett, Nipmuc, and Naragansett joined forces to oust the colonists from the region, and the English, with the help of Mahican, Pequot, and Praying Indian allies, fought back with equal or greater brutality. Between the war’s outbreak in June 1675 and its end in August 1676, up to forty percent of New England’s indigenous population had been killed, died in captivity, or sold into slavery. Five percent of colonists had perished and 67 English towns were destroyed, mostly on the frontier. Quinsigamond Plantation was among them. Hostilities erupted in the vicinity of Quinsigamond in June 1675, when the rebellion’s leader, the Wompanoag grand sachem Metacomet (also known as King Philip), forged an alliance with Horowanninit and the Nipmuc, and destroyed the colonial town of Quaboag (Brookfield). A month later, the constable of Pakachoag, Matoonas, attacked Mendon to avenge the execution of his son by the English in 1671. The region descended into violence. Companies of English soldiers indiscriminately ravaged the villages and crops of both enemy tribes and Praying Indians, and interned captive men, women, and children on the notorious Deer Island and Long Island in Boston Harbor. Meanwhile, Native fighters razed English settlements, among them Grafton and Marlborough. Tiny Quinsigamond Plantation was soon abandoned, and many of its initial settlers, including Ephraim Curtis, joined colonial forces against the rebelling tribes. The empty village was used occasionally as a military outpost until a band of Nipmuc burned it to the ground on December 2, 1675. Upon hearing the news, the fiery Puritan minister Increase Mather interpreted it as a sign of divine wrath. The violence raged through the winter and spring, when it became clear that the English were prevailing. Surviving Natives who were not enslaved or imprisoned gradually retreated from their ancestral homelands. Sensing defeat, Horowanninit of Pakachoag village and 180 followers abandoned their allegiance with Metacomet in July 1676 and entreated the colonial government in Boston for peace. As a sign of goodwill, they captured Matoonas, executed him on Boston Common, and impaled his head nearby, as his son’s had been five years earlier. Their gesture did little to gain the colonists’ trust: of the original 180 men, eleven were executed, thirty sold into slavery, and the rest imprisoned on Deer Island (which they soon escaped). When the war ended in August with Metacomet’s death, Horowanninit and his remaining followers returned to Pakachoag to find the region depopulated. Fewer than one thousand Nipmuc now inhabited what had once been a center of tribal life.

English settlers, too, returned to the area. Quinsigamond Plantation was rebuilt between 1678 and 1686 and renamed Worcester. Houses, mills, a church, a school, and a fort sprang up to replace the ones that had burned during the war, and colonial authorities allotted land to the settlers who moved in. However, the town’s renaissance was short-lived. Native unrest resurfaced in the 1690s, and the beginning of Queen Anne’s war in 1702 sounded the death-knell for the reestablished village. Horowanninit led his fellow Nipmuc in raids against Worcester, causing its residents to flee a second time. In 1713, the English made a third attempt to settle the area. This time, they succeeded. The town of Worcester grew into a thriving city whose diversity belied its bloody beginnings. And although colonial warfare devasted the Nipmuc, they were not exterminated. To this day, members of the Nipmuc Nation call Worcester and the surrounding region home. |

AuthorArchitectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) is working to preserve and redevelop the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as a cutting-edge center for digital innovation. Archives

May 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed