|

That esports is upending the entertainment world and appearing in college curricula is established. But high school?

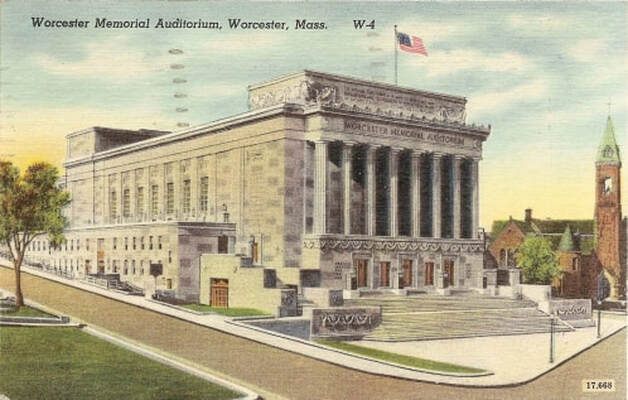

The Washington Post reports that high schools in nine states, including Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island, have officially added esports to their athletics programs. Students train together and compete against teams across the country as they would in conventional athletics - but because esports is web-based, no travel is necessary. Participation opens the possibility of earning a college esports scholarship, but also teaches strategic thinking, teamwork, and sportsmanship, and enables students from across the social spectrum to get to know each other. As the world of high-tech entertainment grows, one thing seems certain: esports will play an increasingly important role in the coming years. And the Aud can be a resource for those who want in. Read the full article here: https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/coming-to-a-high-school-near-you-the-brave-new-world-of-esports/2019/07/22/331919d2-aca3-11e9-bc5c-e73b603e7f38_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.1046ad1cf8d3 The Worcester City Council Economic Development Committee has endorsed the Architectural Heritage Foundation's redevelopment plans for the Worcester Memorial Auditorium. The Committee's support facilitates the execution of a Land Disposition Agreement between AHF and the City later this month, paving the way for the building's eventual sale to AHF or its subsidiary two years from now.

Following a presentation yesterday evening by AHF's development team, Councilor and committee chair Candy Mero-Carlson expressed enthusiasm for reactivating the Aud as an educational, cultural, and entrepreneurial center for digital technology. "This is a pretty exciting night for the city of Worcester," she remarked. "This building has been looked at, re-looked and re-looked at again. We wanted to do everything we could to save it. Working with the colleges on this, this is nothing but a win for the city. I'm very happy to move this forward." Councilor-at-Large Gary Rosen posed several questions about district parking needs and potential, unanticipated hurdles to the project before commenting, "This building, its contents, its history are all in wonderful hands. This is exciting and it's a great project. I support it one hundred percent." Alan Ritacco, Dean of Becker College's School of Design and Technology, attended the meeting and offered insight into the redeveloped Aud's future impact on the city: "There isn't another building like this in New England. This will be a first and put Worcester on the map." For more information on AHF's plans for the Aud, visit the Vision page. Read the Worcester Telegram and Gazette's article on the presentation here: https://www.telegram.com/news/20190618/worcester-auditorium-redevelopment-plan-moves-forward The Worcester Business Journal recently highlighted AHF's pending purchase agreement for the Worcester Memorial Auditorium in an article on recent investment in Lincoln Square. The Aud is one of three historic buildings in the square that are slated for redevelopment by Boston-based companies and organizations. The other two include the former Worcester County Courthouse - currently under construction to become a $58-million apartment project - and the old Lincoln Square Boys Club, potential educational, office, medical, or biotech space. The Journal describes the Aud as "arguably the most historic out of the three," and AHF's project as "the most ambitious."

Read the full article here: https://www.wbjournal.com/article/at-least-170-million-worth-of-redevelopment-projects-could-transform-lincoln-square?utm_source=Newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_content=Three+Lincoln+Square+projects+%7C+Worcester+s+biotech+cluster&utm_campaign=Daily+061119 Following the announcement in the Worcester Telegram of the pending purchase agreement between the City of Worcester and the Architectural Heritage Foundation for the Aud, Worcester media outlets picked up the story. Read the articles below from the Worcester Business Journal and MassLive, and listen to an interview with Worcester City Manager Ed Augustus on Talk of the Commonwealth:

Worcester Business Journal: https://www.wbjournal.com/article/boston-architecture-firm-plans-94m-digital-arts-renovation-of-worcester-memorial-auditorium MassLive: https://www.masslive.com/worcester/2019/05/historic-worcester-auditorium-sold-to-the-architectural-heritage-foundation-for-450000-which-plans-a-94-million-redevelopment.html Talk of the Commonwealth: https://soundcloud.com/talkofthecommonwealth/city-manager-ed-augustus-tells-us-about-selling-the-aud This week, Worcester City Manager Ed Augustus offered his stamp of approval for the future sale of the Worcester Memorial Auditorium to the Architectural Heritage Foundation. His decision came four months after AHF submitted a final report to the City outlining a plan to redevelop the building as a cutting-edge educational and cultural center for for digital innovation, entertainment, entrepreneurship, and the arts. A City Council vote on the future sale authorization is slated for Tuesday, May 28.

The agreement gives AHF two years to complete schematic designs of the project, secure Tier II and Tier III funding, and identify a development partner and building operator before closing. Under a future sales contract, AHF would purchase the Aud for $450,000, or $6 per square foot, facilitating what is expected to be a $94 million redevelopment. The project would preserve the exterior facades, Memorial hall, lobby, Shrine of the Immortal murals, and Kimball pipe organ, while outfitting other interior spaces for digital innovation, competitive gaming, performance, and IMAX-like uses. AHF is excited to continue to work with the City of Worcester on rehabilitating the Aud. We are delighted by the City’s engagement with the project and commitment to the ongoing revitalization of Lincoln Square. Worcester is widely recognized as a leader in technological innovation and education, and the Aud presents an excellent opportunity to connect an historically meaningful building to 21st-century economic opportunities. We look forward to continuing our relationship with the City and the Worcester community to bring this magnificent building back into public use. Read the Worcester Telegram's coverage here: https://www.telegram.com/news/20190523/worcester-agrees-to-sell-worcester-memorial-auditorium-to-architectural-heritage-foundation On May 14, the Worcester Telegram and Gazette published an article on the Architectural Heritage Foundation's discussions with the City of Worcester regarding the Aud. The Telegram states that City Manager Ed Augustus plans to submit a recommendation for the building's future to the City Council on May 28.

Read the full story here: https://www.telegram.com/news/20190514/augustus-set-to-unveil-worcester-memorial-auditorium-recommendation The Worcester Memorial Auditorium is often seen as a white elephant, but across the Atlantic, another adaptive reuse project is demonstrating the rewards of rehabilitating a monumental historic treasure. Château de Gudanes is an eighteenth-century palatial mansion nestled in the Pyrenees, and it has seen better days. Built around 1745 on the site of a 13th-century castle, it was the luxurious residence of several generations of French nobles and members of the bourgeoisie. Confiscated during the French Revolution, pillaged four decades later by "Demoiselles" (local residents protesting aristocratic forestry laws), and used as a children's summer camp after WWII, the Château bears witness to 260 years of French history. In the 1990s, plans to redevelop the building as a luxury hotel fell through when the government designated the site as a Class 1 Historic Monument subject to strict restoration regulations. Exposed to the elements and without a caretaker, Château de Gudanes deteriorated. Fortunately, what appeared to be a preservation failure story may be on its way to a fairy-tale ending. The Château spent four years on the real estate market before a young Australian discovered it online in 2011. His parents. Karina and Craig Waters, were intrigued and traveled to France to view the property. Access to the building's interior was forbidden: part of the roof had collapsed, and the consequent water damage and mold had destroyed most of the 93 rooms. Nevertheless, the Waterses immediately fell in love with the crumbling neoclassical palace and its overgrown grounds, framed against steep limestone cliffs. They purchased the property and began renovations in 2013. Since then, the Château has made a slow, but steady recovery. The Waterses have overcome red tape, hired caretakers, and enlisted an army of professionals, locals, and the just plain curious to rehabilitate the building. They intend to accomplish the work as efficiently and sustainably as possible by recycling original features and using locally sourced materials, such as downed wood from the Château parc. Already they have restored floors and walls that had caved in, repainted frescoes, installed hand-made furnishings in stabilized rooms, and seeded the grounds with wildflowers. Nine bedrooms and two kitchens have been rehabilitated and some underfloor heating installed. Locals have shared their knowledge and skills with the restoration team, including a lady who spent a day in the kitchen preparing dishes her grandmother used to make as Château chef. In fact, the Waterses have opened the property during summer to visitors, who are welcome to stay for up to a week as long as they register for a workshop (topics include patisserie baking and fresco restoration) help with the rehabilitation or cooking, and are willing to navigate the building at night by candlelight (all proceeds facilitate the preservation efforts). The couple summed up their vision for the Château on their website: Our aim is to tread lightly and gently - to preserve the atmosphere and authenticity of the Chateau and region as much as possible. She will be renovated but her rawness, wear and history will not be erased, but instead integrated...The Chateau won’t be a pretentious museum piece, but rather, a place to visit, reconnect with the earth and people, and restore the senses, just like she herself has been restored. It won’t be about overcrowding the walls with paintings or overflowing the floors with furnishings, but will be relatively minimalistic - a place to simply rest, breathe and enjoy the calm. Château de Gudanes has a long way to go before it is fully restored, but in the meantime, it remains an inspiration to preservationists like AHF who are pursuing seemingly impossible projects. Though the Aud is worlds away from this palace in the Pyrenees, it shares certain characteristics: a rich history, astounding architecture, and a passionate local community. If the Château de Gudanes - a behemoth tucked away in a remote, mountainous enclave - can be rehabilitated, then surely the Aud - prominently located in a busy district of Worcester - can, too!

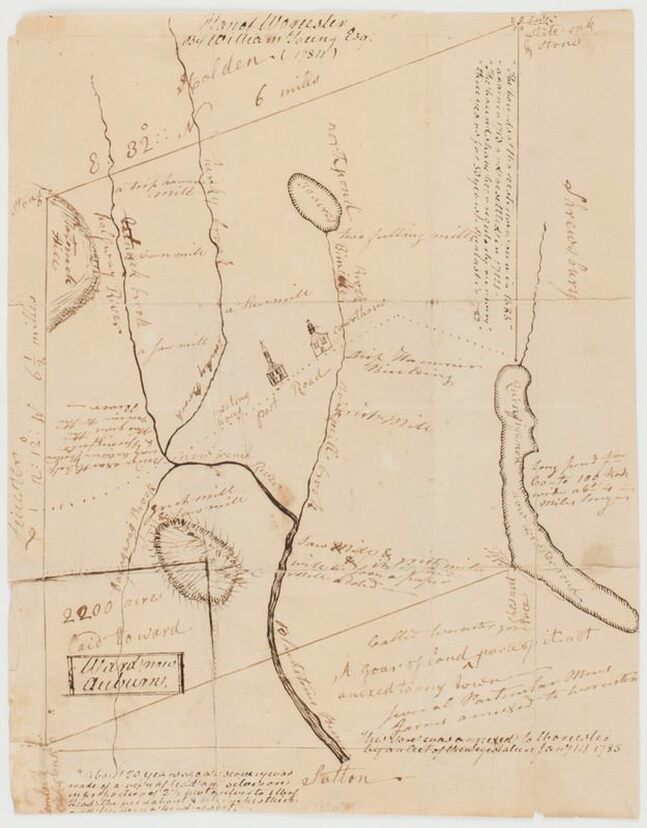

Visit the Château de Gudanes website: https://www.chateaugudanes.com/  Reverend John Eliot (alleged), artist unknown. National Portrait Gallery. Reverend John Eliot (alleged), artist unknown. National Portrait Gallery. How did eight acres of “very good chestnut tree land” become the second-largest city in New England? The answer begins with a colonial property dispute. By the mid-seventeenth century, Massachusetts Bay Colony was outgrowing itself. The towns dotting the coast – among them Salem, Boston, and Cambridge – swelled with thousands of Puritan migrants during the 1630s. Many of these settlers pushed west into Nipmuc territory, lured by vast tracts of seemingly unoccupied land that promised prosperity for their expanding families. New villages cropped up along the Boston Post Road (formerly the Old Connecticut Path): a “praying Indian” town called Natick, founded by “Apostle to the Indians” Reverend John Eliot; Framingham, an agricultural hamlet with a corn mill; and Sudbury, an ancient Native habitation dating back 12,000 years. Meanwhile, the growth of settlements along the Connecticut River created incentive to establish a town halfway between Boston and Springfield that would “unite and strengthen the inland plantations and…be advantageous for travellers.” It was only a matter of time before colonists crossed Lake Quinsigamond (“pickerel fishing place” in Algonquian) to the hilly frontier beyond. The earliest colonial proprietors in present-day Worcester were absentee landowners. Increase Nowell of Charlestown received the first land grant in 1657 – 3,200 acres of valuable meadowland at a time when the agricultural colony was still heavily forested. Another 1,000 acres of meadow were allotted to a church in Malden, and 500 acres to Thomas Noyes of Sudbury. However, it wasn’t until Thomas Noyes, together with three other colonists, acquired Increase Nowell’s property that there was any talk of establishing a “plantation” near Quinsigamond. In 1664, the four men successfully petitioned the colonial government to appoint a committee to survey the territory for a future village. Noyes even managed to get assigned to the task, before his untimely death threw a wrench in the plans. Only in 1668 was a commission finally dispatched to survey Quinsigamond. The committee, which included prominent colonist Daniel Gookin, issued a favorable report. They wrote that the region (present-day Worcester, Holden, and Auburn), though forested and somewhat swampy, contained “very good chestnut tree land” and was “well watered with ponds and brooks.” They also recommended dividing the territory into ninety house lots of 25 acres each, to be apportioned depending on “the quality, estate, usefulness, and other considerations of the person and family to whom they were granted,” and to reserve land for public necessities, including a training field, school, and commons. Unfortunately, nearly all the valuable meadowland was in private hands. The committee’s solution was to void the deeds and annex the land to the future Quinsigamond Plantation. There was just one problem: not every landowner cooperated. Ironically, it was the fate of Noyes’ Quinsigamond estate that delayed colonization of the Worcester area. When Noyes died, his widow sold two 250-acre tracts of meadow to a young man named Ephraim Curtis, also of Sudbury. One tract was in the center of the proposed plantation – precisely where the commission hoped to build a meeting house, minister’s residence, mill, and ten private dwellings. Curtis refused to give up the land and rejected all offers of compensation. He even constructed a house and trading post on his property along the Boston Post Road (now Main Street), a highly visible location that likely further aggravated the committee. For several years, the Massachusetts General Court resisted voiding the property rights of Worcester’s first English settler. The commission forged ahead anyway, enticing thirty men to establish homesteads at Quinsigamond Plantation in 1673. Curtis nevertheless remained a thorn in the commission’s side, and it continued to petition the General Court to settle the case once and for all. Finally, the Court acquiesced. Curtis was allowed to keep 50 acres of his original tract and to select another 250 from nearby house lots.

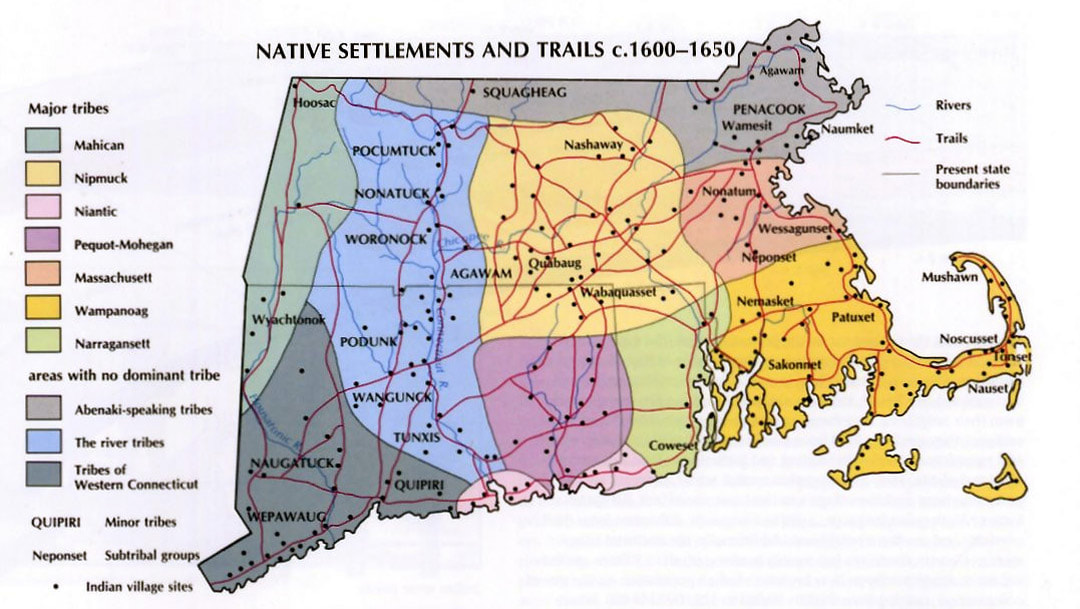

With the resolution of the land dispute, the committee turned its attention to the local Nipmuc who held the original claim to the territory. Three major Nipmuc villages occupied Pakachoag, Tataesset (now Tatnuck), and Wigwam Hills. Daniel Gookin spearheaded an effort to purchase the eight square miles of land from the tribe for Quinsigamond Plantation. In July 1674, he met with Hoorawannonit and Woonaskocha (respectively nicknamed Sagamore John and Sagamore Solomon), who agreed to a purchase price of twelve New England pounds, with a down payment of four yards of cloth and two coats – little more than $2,100 today. With a deed in hand and the Curtis case settled, the commission probably counted their venture a success. But their work was far from done. Tension between British settlers and Native tribes were rising throughout New England as the colonies continued to appropriate indigenous lands. Within two years of the commission’s triumph, Massachusetts would be embroiled in King Phillip’s War, and Quinsigamond caught in the crossfire. A recent Wall Street Journal article highlighted Worcester's Becker College as a national leader in in the rapidly growing esports industry. Esports, which involves live and streamed multi-player video game competitions and is tied closely to game production, has achieved international popularity rivaling that of major league sports in the United States. The industry is projected to grow to $1.7 billion by 2021, and its viewership, to half a billion people. The Journal noted that Becker, already renowned for its program in video game design, is the first institution of higher education in the country to offer an Esports Management degree.

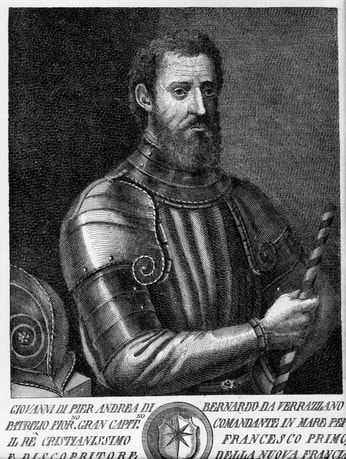

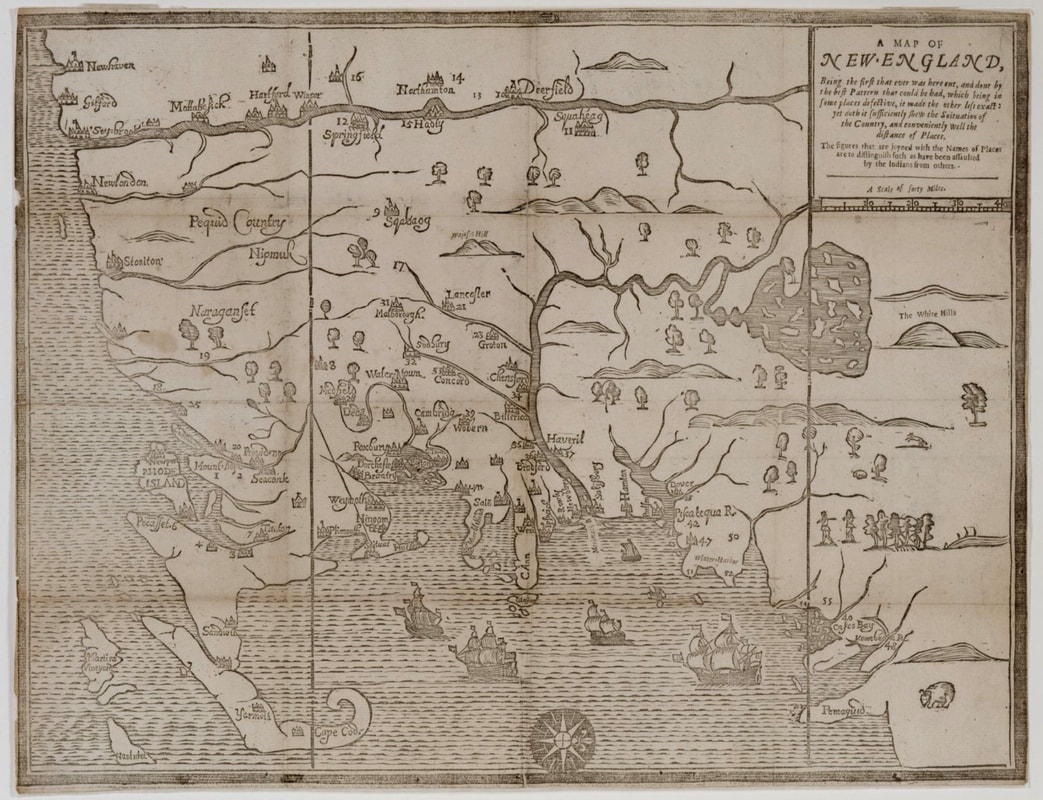

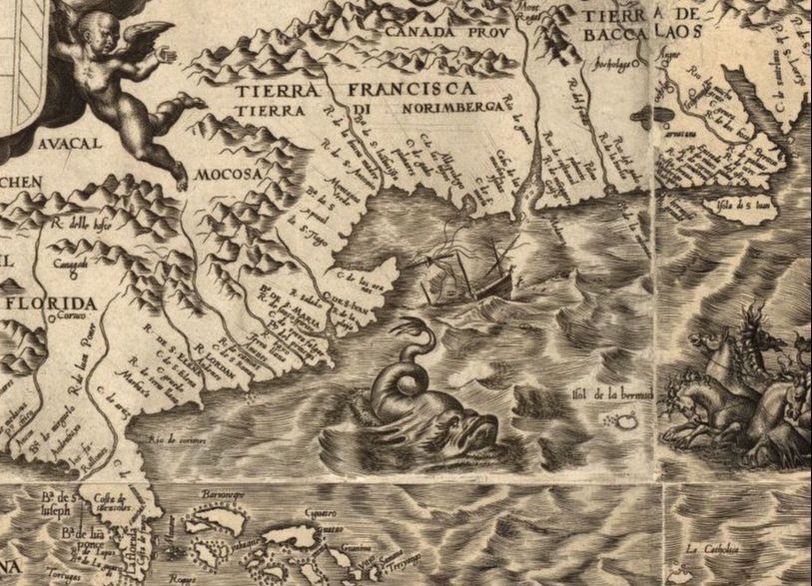

The Architectural Heritage Foundation is partnering with Becker College to study potential uses for the Aud. The school has contributed its expertise in interactive media to developing a vision of the Aud as a cultural and educational institution devoted to technological innovation. Read the Wall Street Journal article here: http://www.wbjournal.com/article/20181210/PRINTEDITION/312079995/1004?utm_source=enews&utm_medium=DailyReport&utm_campaign=Thursday In popular memory, the modern history of Massachusetts began in 1620 with a group of English religious zealots. These men, women, and children are said to have ventured into an unknown region of the New World, a wilderness home to Native Americans who previously had never seen a European face. Massachusetts Bay, the story goes, was discovered, explored, and exploited by English dissidents. But popular memory often plays tricks. The Pilgrims encountered a region that was neither unmapped nor unaware of the wider world. Rather, it had played a role in the imperial Atlantic power struggle for decades. The coastal plains and rolling hills that would become so important in United States history were and remain home to many Algonquian-speaking tribes. Massachuseuck territory, named for the sacred Great Blue Hill (Massachusett, “Big Hill Place”), stretched across present-day Greater Boston. To the west lay Nippenet (“Freshwater Pond Place”), land of the Nipmuck. Their neighbors included the Wampanoag along the Cape; the Pocumtuck, Nonatuck, Woronock, and Agawam along the Connecticut River; the Muheconeok in the Berkshires; and the Penacook and Squagheag to the north. Dozens of long-distance trails connected villages throughout New England, facilitating trade, inflaming rivalries, and strengthening allegiances. Not only people and goods, but information traveled along these routes. When oddly clad strangers appeared offshore, the news would have spread like brushfire.  Giovanni da Verrazzano. Piermont Morgan Library. Giovanni da Verrazzano. Piermont Morgan Library. Five hundred years after Vikings first reached Newfoundland, Europeans became a regular presence in northern American waters. Basque, Portuguese, English, and French fishermen plied their trade off the coast of Canada, and there is evidence that they came into contact with Mi’kmak or Abenaki tribes in Maine as early as 1519. By the end of the century, a steady stream of European fisherman hunted whales and cod around Massachusetts Bay. They probably ventured ashore for fresh water and, perhaps, to trade with Native inhabitants. Official European exploration of New England began with an Italian working for France. In 1524, Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed west aboard La Dauphine in search of the fabled Northwest Passage. Upon reaching the lands of Siouan-speaking tribes (North Carolina), he kidnapped a boy to bring back to France and then turned north, hugging the coastline. He ventured into the areas of Mahican and Nahigansett (New York and Rhode Island), sailed past treacherous sandbanks and a “high promontory” that he named Pallavisino (Cape Cod), and proceeded to Wabanakhik (northern Maine), before ending his expedition in Beothuk territory (Newfoundland). Like many Renaissance voyagers, Verrazzano portrayed North America as a resource-rich idyll; present-day Rhode Island was “suitable for every kind of cultivation – grain, wine, or oil,” while Cape Cod “showed signs of minerals.” Notably, he described Natives’ varying attitudes towards the Europeans. Most, including the Narragansett, were “generous” and “gracious;” some were fearful; and the Abenaki were downright hostile: they insisted on trading “where the breakers were most violent,” attacked sailors who came ashore, and mooned Verrazzano’s crew upon its departure. Such behavior suggests that Maine tribes had a painful encounter with European fishermen even before La Dauphine arrived. Their neighbors to the south would soon have similar experiences. Exploration increased in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, spurred by stories of a northern El Dorado. Maps of the New World increasingly identified present-day Maine and southeastern Canada as the mythical Norumbega, a region of vast wealth that captured Europeans’ imaginations. In a possibly fictive and certainly fanciful travel account published in 1589, the sailor David Ingram claimed to have journeyed overland from Florida to Cape Breton and to have visited Bega, a city replete with “rubies six inches long,” pearls, and gold. The rumors lured Samuel de Champlain across the Atlantic in 1605. Though he discovered neither Norumbega nor the Northwest Passage, he did produce one of the earliest maps of Boston Harbor and an account of the people living there: “We saw in this place a great many little houses, which are situated in the fields where they sow their Indian corn. Furthermore in this bay there is a very broad river which we named the River Du Gas.” To the Massachuseuck, this river was the Quinobequin. To the Puritans, it would become the Charles. Europeans continued to frequent Massachusetts Bay in the years leading up to the founding of Plymouth Colony. Henry Hudson, John Smith, and Thomas Dermer all made the voyage, with disastrous consequences for Native peoples. In 1614, Smith’s associate Thomas Hunt kidnapped twenty-four members of the Patuxet tribe, including the renowned Tisquantum (Squanto), to sell as slaves in England. Hunt’s action upended the delicate trade relationship between the tribes and the English, initiating a period of open hostility. Indeed, local inhabitants might have stymied later colonization attempts if not for an invisible enemy that ravaged New England populations prior to 1620.

With the boatloads of Old World fishermen and explorers came an influx of Old World pathogens. Intermittent epidemics may have begun as early as the sixteenth century. Scholars debate which diseases swept through New England before the Pilgrims arrived; leptospirosis seems most plausible. One thing is clear, however: between 1616 and 1619, a plague decimated Native tribes. In 1619, Tisquantum returned home to a dead village. Scholars estimate that disease claimed the lives of 75-90% of eastern Massachusetts peoples over the course of the seventeenth century. The survivors were hard-pressed to repulse the thousands of colonists who poured into the region – and with whom the recorded history of Brighton and Worcester begins. |

AuthorArchitectural Heritage Foundation (AHF) is working to preserve and redevelop the Worcester Memorial Auditorium as a cutting-edge center for digital innovation. Archives

May 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed